As the author notes by rephrasing Neil Postman’s famous quote: Information has become separated from meaning. The sheer volume of available information and it being rendered in a message not comprehensible to the hunter & gatherer brain which longs for storytelling and physical experiences instead of STEM examinations and binary codes, make information useless. The same is true for this book and the author misjudges the reality of what his readership is capable of. Despite confirming that small libraries are much more useful than larger ones, he concludes this popular science title with more than 400 endnotes and this comment: Listing every paper I read would make the endnotes section ten times longer, and far less useful to the general reader. I think it was Huxley who said that completeness is not nothing to add, but nothing to take away.

Levitin is one of the foremost cognitive psychologists on this planet, an accomplished musician, a high end business consultant and in general a polymath. He lays out a plan in this book on how we are supposed to organize our lives and does so with astonishing eloquence and erudition. Strangely though, he writes already in his introduction that we organize our minds in different educational disciplines to deliver ever higher levels of achievement, to provide an edge in a world that is increasingly competitive.

The Organized Mind Lacks Wisdom

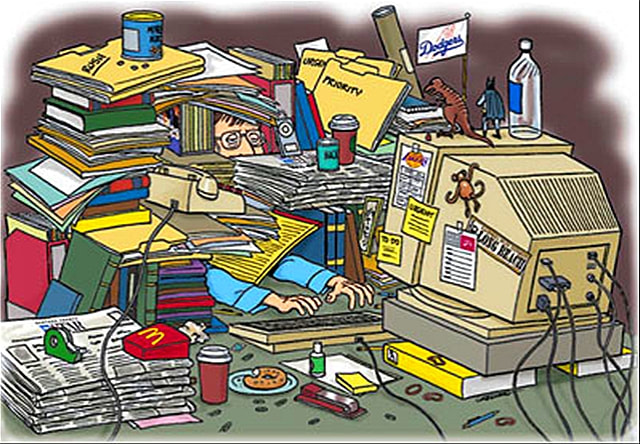

I honestly enjoyed reading this book despite its scholarly style, because it is throbbing with so much information and knowledge. But at a certain point I kept asking myself if it doesn’t lack essential wisdom. A question kept recurring to me: Can we really burden all of humanity with the information structuring techniques of CEOs, extreme athletes or genius musicians, or is this just too much for an average person? Shouldn’t we shift the focus from being a psychologist who analyses the improved functionality of the human brain to the perspective of the sociologist who captures the picture at large to understand what causes the information overload and if this suffering is indeed necessary? Levitin appears as a physician or mechanic applying the perfect understanding of a machine (in this case the brain) to conduct a complex surgery on the sick mind, but fails to understand the etiology of this epidemic information overload.

I wish Levitin would have written a book which takes the burden off the average person (like Tom Hodkinson took the burden of parenting from my shoulders) instead of writing a book which tells people how to become as effective as a fortune 500 CEO. It tunes into the general dissonance of our competitive knowledge economies, which lack harmony and cooperation. Levitin sets a tone which goads the reader into a mindset of wanting better brains despite confirming that our brains are not made for such enormous amounts of information: Its helpful to understand that our modes of thinking and decision making evolved over the tens of thousands of years that humans lived as hunter-gatherers. Our genes haven’t fully caught up with the demands of modern civilization, but fortunately human knowledge has – we now better understand how to overcome evolutionary limitations.

Levitin comes thus across as yet another scientist who seems to prefer a transhumanist future over humankind at peace with its mammal nature. He puts his reader on track to desire a gadget here and an implant there to become at least by means of artificial improvement as competitive as the most successful members of society. By doing so he joins the atheist visioning of academic writers like historian Yuval Harari, who described the future of neural enhancement in his last book Homo Deus.

The first humans who figured out how to write things down around 5000 years ago were in essence trying to increase the capacity of their hippocampus, part of the brain’s memory system. […] We are [since then] off-loading a great deal of the processing that our neurons would normally do to an external device that then becomes an extension of our own brains, a neural enhancer. […] Once memories became externalized with written language, the writer’s brain and attentional system were freed up to focus on something else.

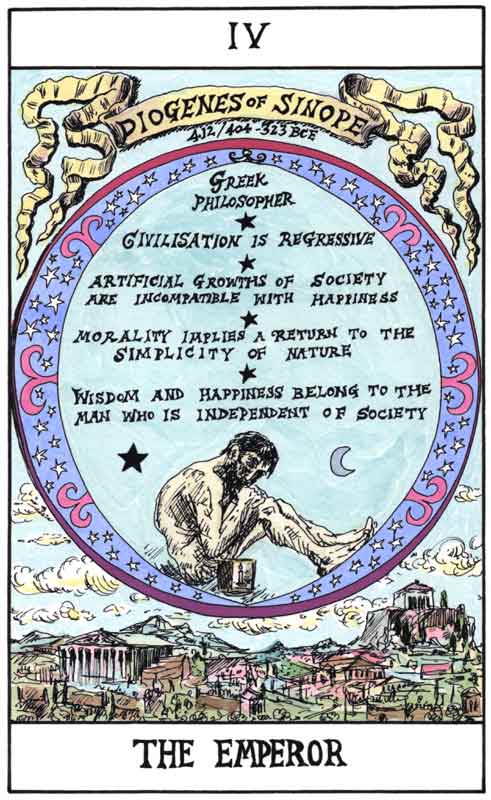

Henry Kissinger mentioned in World Order which was written in the same year as The Organized Mind, that philosophers and poets have long separated the mind’s purview into three components: information, knowledge, and wisdom. The Internet focuses on the realm of information, whose spread it facilitates exponentially. Ever more complex functions are devised, particularly capable of responding to questions of fact, which are not themselves altered by the passage of time. Search engines are able to handle increasing speed. Yet a surfeit of information may paradoxically inhibit the acquisition of knowledge and push wisdom even further away than it was before. Levitin fails to acknowledge that it is more wisdom what we need now, not more successful people who can organize more information in a shorter time to survive in an ever competitive society.

Missing a Solution for how to Teach Children

A close look into Levitin’s table of content reveals that there is a lack of organization, a blind spot or even a big question which he was not able to answer when structuring his work. I don’t want to sound critical. I would have never been able to bring together this vast amount to data and studies which Levitin has managed to pack into this book. He deserves full credit therefore. The three part structure reveals though that there is something missing. Part I provides a brilliant introduction to the history of cognitive overload over the last 5000 years and explains the neuroscience of attention and memory. Part II explains in five chapters how to organize our homes, our social world, our time, our decisions in moments of threat and danger, and the business world.

So far so good. I couldn’t think of a better way to structure these two parts. But while Levitin goes into very details of how to organize our lives, e.g. by explaining at extreme length how emails can be efficiently handled, he covers in part III what we have to teach our children and “everything else” superficially. Its telling that he writes about the power of the junk drawer in the same section, which addresses in my humble opinion the most pressing question of all: how to save our children from this insanity.

Part One

- Too much information, too many decisions: the inside history of cognitive overload

- The first things to get straight: how attention and memory work

Part Two

- Organizing our homes: where things can start to get better

- Organizing our social world: how humans connect now

- Organizing our time: what is the mystery?

- Organizing information for the hardest decisions: when life is on the line

- Organizing the business world: how we create value

Part Three

- What to teach our children: the future of the organized mind

- Everything else: the power of the junk drawer

Educator Neil Postman understood the true challenge with societies suffering from information overload in all its clarity already back in the 1980s. In a 1990 speech titled Informing Ourselves to Death he argued that our society relies too heavily on information to fix our problems, especially the fundamental problems of human philosophy and survival, that information, ever since the printing press, has become a burden and garbage instead of a rare blessing.

According to Postman’s speech, "the tie between information and action has been severed. Information is now a commodity that can be bought and sold, or used as a form of entertainment, or worn like a garment to enhance one's status. It comes indiscriminately, directed at no one in particular, disconnected from usefulness; we are glutted with information, drowning in information, have no control over it, don't know what to do with it."

Levitin adds the chapter of what we ought to teach our children to the junk drawer, because he has on the contrary to organizing our business world or our homes no answer to this question. He understands the neurological science, but isn’t able to connect the dots. He writes that children are more likely to want immediate gratification, and they are less likely to be able to foresee the future consequences of present inaction; both of these are tied to their underdeveloped prefrontal cortices, which don’t fully mature until after the age of twenty (!). This also makes them more vulnerable to addiction.

Education is though not only about what we teach children in school, but about the frame conditions in which we bring them up. Raising our offspring in an addiction culture will result in lots of addicted adults. Levitin recommends to strengthen so-called foundational concepts and habits of mind. They are mental habits and reflexes that should be taught to all children and reinforces throughout their high school and college years.

Training children in these habits, but letting them grow up in a culture which is an addiction mine field makes Levitin look like a Don Quixote and makes me recall The Matrix: we need to be taught critical thinking and sound habits of mind, there is no doubt about it, but as long as we live in a culture which places each individual already in its early childhood years into an addiction cocoon, which grows thicker as we grow older, it won’t be possible to construct a sane society.

Levitin contradicts his recommendation of teaching foundational concepts and habits of mind in the very same book, where he writes only a few paragraphs earlier that the primary mission of teachers must shift from the dissemination of raw information to training a cluster of mental skills that revolve around critical thinking. Teachers who succeed in doing so must be wizards of neurology able to change the human brain development. How are we supposed to teach children critical thinking, if the very brain region for critical thinking, the prefrontal cortex, is not yet fully evolved and is under permanent attack to be rendered useless by excessive screen time, sugar floods and many other habits of consumption which civilization pressures us into?

Neil Postman compared contemporary society [of the 1980s and that’s even more so true today] to the Middle Ages, where instead of individuals believing everything told to them by religious leaders, now individuals believe everything told to them by science, making people more naive than in Middle Ages. Individuals in a contemporary society, one that is mediated by technology, could possibly believe in anything and everything, whereas in the Middle Ages the populace believed in the benevolent design they were all part of and there was order to their beliefs.

Critical Thinking vs. Subtle Trust

I wrote in the beginning that Levitin is a polymath. Reading his biography I was truly in awe about his life trajectory and the self-confident decisions he made. He is in every aspect himself an organized mind and an exemplary CEO – at least in regard to shaping his identity and self. He studied applied mathematics at MIT, dropped out, pursued a career as musician, sound engineer and record producer, only to return to university in his thirties. He completed a fast track PhD in cognitive science at Stanford and one must wonder where the energy, motivation and above all the financial support came from. It might have helped that Levitin is the son of an accomplished businessman and university professor, and a hyper-productive novelist, who survived the holocaust; indicating an upbringing in an non-religious Jewish-American environment which endowed Levitin with an excelling nature and outstanding conditions of nurturing. The Organized Mind was dedicated to Levitin’s parents “for all they taught me.”

Whenever I read nowadays a non-fiction book, I ask myself by what the authors were driven and from what perspective did they start off. Why did they spend literally hundreds of hours researching and writing and from which point of view did they look at the very subject of the book? Levitin was without doubt born into one of the sunniest places on this planet. He did not only grow up in sunny California in the boon years of US economic growth, but was blessed with abundant material support. Starting from such a high level of living standard and accomplishment, one is easily tempted to raise expectations and desire more.

I can’t say anything about the emotional and spiritual support Levitin received from his parents and his extended family, but it seems to a certain extent that his search for the perfectly organized mind is the result of growing up in an atheist environment, which must have been influenced deeply by the ordeal his Berlin born Jewish mother underwent after fleeing Europe and starting a new life in the US. I believe it’s important to observe that Levitin makes not a single reference to how the spiritual outlook of a person or the emotional baggage of one’s family affects the structure of the mind; neither does he mention with a single word how our nutritional habits shape what we think, and yes, what we are.

A few months ago, I wrote an essay about the neurology of faith, love and hope and arrived at the somehow mystic interpretation of Juvenal’s quotation mens sana in corpore sano, i.e. a healthy mind rests in a healthy body. My interpretation was spiritus sanctus in corpore sano, i.e. a saint spirit rests in a healthy body - if, and only if, the mind opens itself to the guiding force of God. I recall now yet another quotation from writing teacher Julia Cameron, which is related to this train of thought: Be alert, always, for the presence of the Great Creator leading and helping my artist.

Both quotations indicate that there is yet another force at work in organizing information and making it available at one’s fingertip. It’s a force which is beyond the understanding of our little minds which are restricted by the limitations of our petty and fearful egos. It is the mind at large as Aldous Huxley called it in The Doors of Perception. Levitin somewhat knows about this mind at large as he quotes Albert Einstein who said “The greatest scientists are artists as well.”, but he adds it to the last chapter in his book: Everything Else – The Power of the Junk Drawer.

This might all sound as if I don’t appreciate Levitin’s work. I sincerely do, but I don’t think that his conclusions will solve the problems which humanity currently faces, in particular it won’t solve the most crucial question: what to teach our children? I say this, assuming that the reader agrees that we have done something wrong in the past, looking at environmental and social destruction all over the planet. Training our offspring to be even more competitive won’t be the solution. As His Holiness, the Dalai Lama said: The planet does not need more successful people. The planet desperately needs more peacemakers, healers, restorers, storytellers and lovers of all kind.

While successful people tend to neurotically organize their intellectual mind and their material environment, while they hold tight onto their critical linear thinking, healers, storytellers and lovers are guided by subtle trust and the ability of letting go. Levitin knows about this and strangely enough concludes his book - after dissecting like nobody else before him how we organize the phenomenal world – with faith: The key to change is having faith that if we get rid of the old, someone or something even more magnificent will take its place. My wise wife puts this into even simpler terms: 旧的不去新的不来, i.e. if the old doesn’t go the new won’t arrive.

Many of the world’s problems – cancer, genocide, repression, poverty, violence, gross inequities in the distribution of resources and wealth, climate change – will require great creativity to solve. Levitin suggests non-linear thinking and the daydreaming mode are much underestimated qualities of human problem solving and one is again tempted to read between the lines that this is the way how a cognitive psychologist writes scientifically about how God manifests himself in our minds. Levitin quotes once again Einstein saying Imagination is more important than knowledge and continues every writer wonders where fictional ideas come from, but avoids an answer to the question which is pregnant throughout his last junk drawer chapter: what is the source of creativity and imagination?

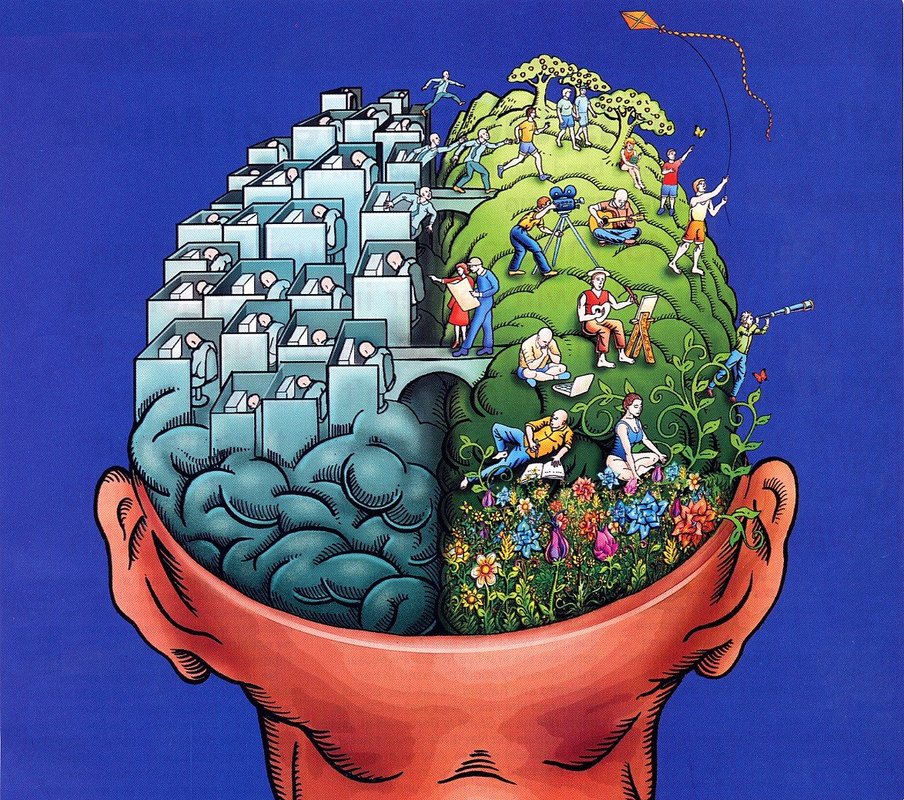

It is strongly recommend to read on this account My Stroke of Insight by neurologist Jill Bolte-Taylor. The accomplished brain scientist experienced a brain stroke at age 37 and witnessed how her left hemisphere, the one which is responsible for our linear, task-positive thinking and which is thoroughly analyzed by Levitin, shuts down. What she is left with is her right hemisphere and although she enters a near death experience she realizes that there is something more at work than her small mind and fearful ego.

If we want to solve the world’s most pressing problems, we need to remember two things. Firstly, Levitin’s most central thesis, that the twenty-first century’s information problem is one of selection. Secondly, that it is not us who can make this selection. Levitin writes, that there are really only two strategies for selection in the face of this [information flood] – searching and filtering. Together these can be more parsimoniously thought of as one strategy, filtering. And the only variable is who does the filtering, you or someone else. When you search for something, you start out with an idea of what you want, and you go out and try to find it.

I have come to the conclusion that whenever I go out and try to find something that I end up being overwhelmed by the multitude of choices to make and the amount of information to digest. Since I have submitted my life to God and the great filtering system of the mind at large, I feel like I have entered a smooth operation mode which reduces the amount of information organization. I organize only what is necessary for the next days, because I can trust that somebody else takes care of the journey and its destination. Levitin’s work has scientifically confirmed that I am on the right track. Subtle trust rules over critical thinking; but we need both. Otherwise we either turn paranoid or superstitious and naïve.

One might add to this on a cynical note that Levitin is not a very critical thinker. He writes 400 pages in small print, which would turn out to be at least 600 pages in standard font size, about many interesting details. He is completely ignorant though of political realities, when he refers to the 9/11 incident or the Iraq war. One wonders if he is naïve or if his position in one of the most respected universities on the North American continent force him to avoid the truth about the US war against its own citizens and the economic growth paradigm behind war against other countries.

Useless But Indispensable

If I started with this review by saying that reading this book is indispensable, but you might very well find it useless, I would like to confirm for those who are not interested in cognitive psychology that this is most likely true. Levitin makes though a few very wise remarks on the last two pages, which are useful to everybody. He writes: One’s junk drawer, like one’s life, undergoes a natural sort of entropy. Every so often, we should perhaps take time out and ask ourselves the following questions:

- Do I really need to hold on to this thing or this relationship anymore? Does it fill me with energy and happiness? Does it serve me?

- Are my communications filled with clutter? Am I direct? Do I ask for what I want and need, or do I hope my partner/friend/coworker will psychically figure it out?

- Must I accumulate several of the same things even though they’re identical? Are my friends, habits, and ideas all too similar, or am I open to new people’s ideas and experiences?

Getting organized can bring us all to the next level in our lives. It’s the human condition to fall prey to old habits. We must consciously look at areas of our lives that need cleaning up, and then methodically and proactively do so. And then keep doing it.

Every often so, the universe has a way of doing this for us. We unexpectedly lose a friend, a beloved pet, a business deal, or an entire global economy collapses. The best way to improve upon the brains that nature gave us is to adjust agreeably to new circumstances. My own experience is that when I’ve lost something I thought was irreplaceable, it’s usually replaced with something much better. The key to change is having faith that if we get rid of the old, someone or something even more magnificent will take its place.

Let’s hope that we find that key to get rid of greed, capitalism and economic growth. There is something much better waiting for us. To find the key it helps to declutter radically in the material, intellectual and the emotional world. Free our children from force-fed education and trust that the last two decades of research on the science of learning have shown conclusively that we remember things better, and longer, if we discover them ourselves rather than being told them explicitly. Zen masters speak in riddles because they let the disciple set neuro-markers on his own; and thus the cup must be empty to be filled.