| on_migration_and_metamorphosis.pdf |

In March 2016, I participated in an odd event under the title: break, change, departure. It was a three-day retreat for Christian, German men on a remote Hong Kong island in a Don Bosco cloister. Having emotionally denounced my Christian confession at age 16 while still in catholic boarding school, where Christian faith was practiced without proper reflection on the basis of coercion only, I had been traumatically conditioned to circumnavigate such kind of conventions.

Raised in a Christian culture and rejecting it early, I tend to perceive religious communities nowadays as systems within society at large. Rejection or even labelling the entirety of such communities as wrong, would put me into the same mindset as some fervent adherents of such religions: exclusion instead of integration. I therefore try to use them as platforms from which one can navigate into social realms, that open up new perspectives upon the other and oneself.

However, having myself labelled both, as native Austrian not German and not Christian by confession, it took me a considerable mental effort to sign up and effectively attend that retreat. My gut feeling told me though, that despite the setting, this was the thing to do at that specific moment. The title itself radiated some magical attraction, because I felt that a period of fundamental change was lying ahead in my own professional trajectory.

In hindsight, I acknowledge that this retreat-seminar prepared me for a major transition, which could be described as a migration in both physical and spiritual dimensions; and without doubt, I am truly grateful for having been part of it; if not for anything else, then for the simple realization that a considerable part of myself is both Christian and German - the latter was even confirmed by the Genographics DNA test, which I recommend dearly.

Labelling oneself deprives us from experiencing the complete spectrum of our identity and insofar it is a destructive mindset which falls short of taping into the potential available; the same is true for labelling others, colleagues, strangers & migrants, in regard to the potential interaction with them. My interaction with German Christian men produced some refreshingly new friendships and gave me valuable feedback about until then unknown layers of my own identity.

What I want to share here are my general reflections on the varieties of migration, which were triggered by the lectures and conversations of that weekend; and moreover the specific burden modern man has to cope with a world of accelerated change and infinitely increased information. This year, there is a quite personal connection to the issue at hand. Some might remember last year’s CNY mail about the psychological phenomenon of mid life crisis. I concluded that we might take a sabbatical in the foreseeable future as a preventive strategy to avoid MLC. What I did not know: I should be relieved of my duties as Fronius China Managing Director only two months later and would be rewarded for more than five toilsome but extremely educative years with a 14-months sabbatical.

Since May 2016 I spend my days full time writing on personal and organizational development in a Chinese context; and I struck a deal with my HQ to draft a corporate training course based on Chade Meng-Tan’s Search Inside Yourself bestseller to finance this period. Not everything was smooth about this deal, and I had to digest some emotional scars during the first weeks of my new found freedom, but in hindsight I am grateful for this opportunity to grow and transform without having to worry about an income.

In terms of my professional future a wide spectrum of opportunities opened up, and I am still in the process of figuring out what I will do after the sabbatical oscillating between doubt and faith. I noticed, too, that there is a correlation between security and interest. The higher my interest in a specific career, the less in particular financial security it provides. Erich Fromm might have been right by saying that the quest for certainty blocks the search for meaning.

You might also remember that I made last year extensive reference to Viktor Frankl’s book Man’s Search for Meaning, where he writes: For success, like happiness, cannot be pursued; it must ensue, as personal dedication to a cause greater than oneself or as the by-product of one’s surrender to a person other than oneself. If only pleasure is sought after, genuine and lasting happiness can’t ensue. I concluded then: If all psychological discontentment is rooted in stagnation, so it must be for midlife crisis. There are probably many more reasons why midlife crisis kicks in, but assuming that our children leaving us alone with ourselves -and thus again inducing a change in our identity at a much later stage in our life- is a main source of suffering, we are advised to embrace this period of transition. If we have experienced growth when becoming parents by surrendering to something larger than ourselves, it seems to be a wise approach to do the same once again by e.g. signing up to a non-profit initiative or adding purpose to our jobs.

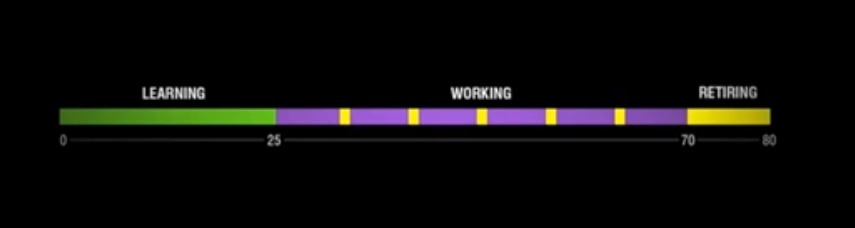

Sagmeister proposes a fundamental change in lifestyle design. He explains that we generally spend 25 years of our life in education, 40 in work and if things go smooth another 15 in retirement and suggests to take five years out of retirement and distribute those years evenly over the duration of our work life. He argues that it is better to devote every seven years of work, rather one year to oneself than 15 years of retirement to one’s grand children. But what he suggests is not an egoistic undertaking, but an encounter with one’s creativity and the connection of the self with the creative ground; a contemplative adventure which reveals what really matters.

Meaning and Passion.

In particular, when we are not anymore driven by urgent economic needs, instilling purpose to our lives, can turn though into quite a tricky task. How do we actually find our purpose and how does one surrender to something larger than oneself as Frankl insinuates? I happened to run into a brief article by Scott Wilhite on the Soul-Quieting Power of Purpose, in which he refers to a TEDx talk by Adam Leipzig. Film producer Leipzig claims that one only has to answer five simple questions to figure out one’s purpose:

- Who are you?

- What do you love to do?

- Who do you do it for?

- For the people you do it for: What do those people want or need?

- And what did those people get out of it? How did they change as a result?

This fundamental flaw is related to the assumption that all people can genuinely love have passion. Loving is though a competence which is instilled into human beings mainly by being loved during early childhood which they then learn by simple imitation and reciprocity. It can also be learned at a later stage as e.g. Erich Fromm pointed out in The Art of Loving, but like all learning is then a much harder subject to get good grades in: you can’t teach an old dog new tricks.[1] Love is ideally instilled into our bodies and then finds its way over our minds into our activities and professions.[2] It was Jung, who implied that loving as a competence is the source for creativity by writing that The creation of something new is not accomplished by the intellect but by the play instinct acting from inner necessity. The creative mind plays with the object it loves. Those amongst us, who have never properly developed this practical-physical competence, because it first had to be instilled as a theoretical concept into their minds, won’t be able to answer Leipzig’s questions nor will they be able to find their purpose by this method.

I see though a deep truth in the quote at the end of Wilhite’s article, because it points at the second source of how we can figure out our life’s purpose: Never give up on something you can’t go a day without thinking about. Those who have not been fortunate enough to learn the competence of loving early in their lives have another source for identifying their purpose apart from their waking dream: their innermost trauma. Andrew Solomon describes that it takes quite an arduous journey of self-transformation to unlock the positive energy of trauma. Some take it deliberately like Ellen MacArthur who chose to go on a solo around the world sail to understand her calling; others are brutally pushed into it like Ismael Nazario who had to spend years in prison and 300 days in solitary confinement. Only those who take it, can answer the questions Did you live? Did you love? Did you matter? at the end of their days with yes. This yes corresponds with what Erickson called ego integrity and is opposed to despair if one fails to integrate his life’s thoughts and deeds into his personality from a retrospective POV.

Migration and Community.

We were a group of roughly 25 men back then in March 2016, aged 35 to 60, and despite our different educational and social backgrounds we all had two things in common: we were German native speakers and we worked and lived in China since several years. It was this common ground, which made us attend this retreat in the first place, but it was also this common ground which streamlined our psychological horizon. The challenges of migration in the widest sense, from employment into retirement, childhood into adolescence or from one job to another, come in an international setting usually with a plethora of other issues one has to deal with, most commonly it involves a change of location. I could sense from the discussions that all these weekend monks were facing the one or other transition in their own specific way: with joyful anticipation, doubt, regret, anxiety or even fear. However, we all met that weekend to strengthen our faith.

The secluded setting of the Don Bosco cloister contributed substantially to the entire experience, but probably the community which grew rapidly amongst complete strangers, who have a common purpose for a few days, was even more important. Two priests who guided us as facilitators – that’s how you would have to call them in new speak - did a great job within their own religious and cultural framework. They provided a daily routine, which gave all participants a clear structure to enjoy the retreat and made it easy to get to know each other. Joint meals were concluded with washing the dishes in an open air kitchen. We would convene in one of the chapels for a short worship after breakfast and dinner. In between the meals, we had every day three 2 hour workshops with an impulse talk as starting point and an open discussion following en suite. There still was time left for a stroll or run around the island once a day. The weekend felt like a light, but well packed rucksack, one is happy to carry.

It is surprising that such retreats are not organized by psychologists or non-religious facilitators respectively. But then, maybe they are, its just me not knowing of them. I sense though, not only within myself but for humanity at large, a need to be guided in phases of transition, in particular in a world of accelerated change. Such guidance can’t be really provided in weekly religious assemblies of people who do not have the time to focus on neither the now nor their life’s horizon. Neither can psychotherapists in weekly one hour sessions provide transformative counselling; quite on the contrary does much therapy turn into just another ego centered routine, which lacks the collective experience.

I do also believe that traditional confessions loose their adherents in economically advanced societies, because their shepherds lack relevant knowledge. In times of neurology, neurological biochemistry, positive psychology et cetera, I am convinced that faith has its place in our lives, but it needs to be supplemented with the scientific discoveries of the past two centuries, in particular of the past five decades. Podcasts like Waking Up with Sam Harris, a neurologist by training and declared pagan or the philosopher Alain de Botton’s School of Life, cater to this modern, post-conventional audience, but they do so only virtually.

Transcending our individual livelihoods, we witness a transformation at a much larger scale brought upon us by means of accelerating technological progress. The globalization and cybernation of our societies has a similar if not even more radical impact on our work and live than the invention of electricity. Against this backdrop man is constantly challenged to reinvent himself. Old patterns of behavior and thought are largely obsolete, and naturally man looks for new identification figures who can show us the path ahead.

I mostly had troubles with clergyman of whatever confession, because they tend to stick to their scriptures like nationalists to their turf and won’t accept different perspectives. Considering that religions are nothing but aspects of regional cultures, developed in the shape of a mindset of certain peoples, they usually fail to encompass all that is and thus also fail to give answers to an increasing number of polyglot cosmopolites. As we move towards a universal consciousness our shepherds have to upgrade their hard and soft skills, if they don’t want to be left behind by their flock. The year 2000 movie Keeping the Faith intrigued me deeply, not so much because of the picante ménage à trois between a catholic priest, a Jewish rabbi and their joint childhood girlfriend, but because of their progressive sermons and humorous, but passionate customer care. There is no schism between science and theology, they need to merge and modern priests ought to be a mixture between a scientology officer, a Sufi mystic and a molecular engineer. But who can be such a wizard?

Individuals, even polymaths are limited to certain competences. That’s why there is a special value in community, where several individuals can pool their competences of neurological astuteness, focused pragmatism, molecular precision, cogent rhetoric and icebreaking humor, if they are bound by some spell of mutual benevolence and gratitude to experience a few hours together in the pursuit of collective learning. It is after all collective learning, not the single wizard, which defines humanity.

I enjoyed it therefore to listen to layman from different walks of life during the official sessions of that weekend; to learn about their personal views on subjects of change, transformation and development. It became also apparent that the time in between the official program was an equally important part of that weekend, where against the backdrop of a structured convention spontaneous encounters happened, which have in my memory an equally lucid place. Only the platform of the community can enable such spontaneous and often cathartic encounters, where the roles of teacher and student, of giver and taker are in constant flow. The planned meeting with a single friend, a paid therapist, the HR manager or a man of God in the confession cabin can rarely catalyze such moments. We need to be open to the mind at large, as Aldous Huxley put it, to engage in such encounters, albeit not through the intake of psychedelics, but through the submission to community with others. Somehow man gets ever more connected through technology, but simultaneously alienated and isolated in the physical world.

Thinking about the relevance of community makes me recall an essay by Siri Hustvedt, which she titled Freud’s Playground. She describes Freund’s concept of the space between people, where people spontaneously interact like on a Tummelplatz, the German word for a fair-like playground, and cites Dutch historian Johan Huizinga, a 20th century Yuval Harari, who published 1938 homo ludens, where he argues that all culture is a form of play. Two people can play combative games like chess or go, but they can’t participate in the complexities of games with several participants. A chess player might be able to memorize hundreds of tactical move clusters, but wouldn’t be able to predict the next move of several unknown participants. That’s why both trust and faith can be better learned in communities; and that’s why one or two people are not enough to constitute a culture.

Highly individualized and highly regulated cybernetic societies reduce the opportunities to truly engage in communities, they destroy the playgrounds on which the creative minds play with the objects they love, or, if one wants to put it like Erich Fromm in The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness: they convert organic into mechanistic cultures which deprive us of the ability to love. Hustvedt therefore rightly agrees with the philosopher Martin Buber, who said that psychological illnesses do grow up between people, not within them. It’s the in between, where our cultures blossom or whiter.

Migrants and Fugitives.

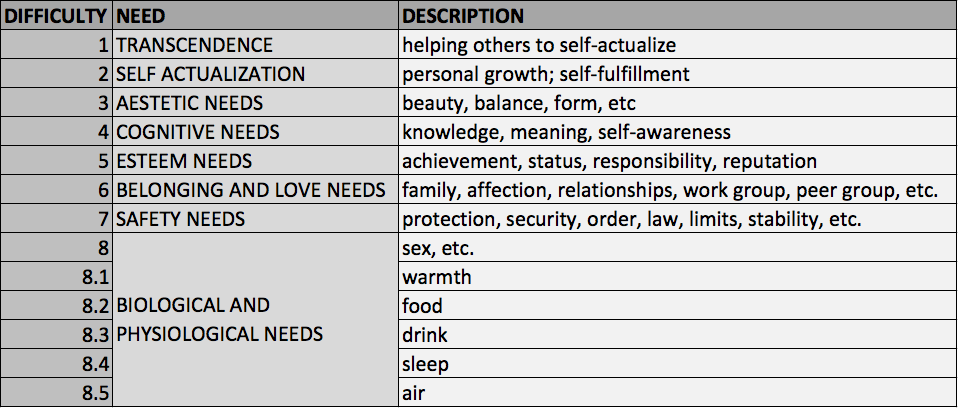

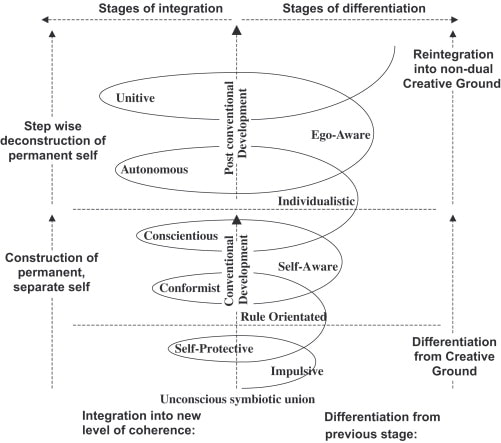

A fellow weekend monk mentioned during one of the workshops a FAZ interview with the psychotherapist Wielant Machleidt who analyzed the psychological challenges of fugitives during the “European” migration crisis. He rightly describes the entire human life as one long migration; and we remember last year’s detailed explanation how the developmental psychologists Erik and Jane Erickson identify eight phases of psychosocial crisis from birth to death. Machleidt concludes that fugitives who have to integrate into a host society undergo a second adolescence, which he calls cultural adolescence. It is a phase which requires the individual to detach itself from the parent surrogate of the originating state and society to form a new identity defined by both the originating and the host society.

Jung would have called the process of taking a step back from one’s own cultural conditioning individuation and would have welcomed additional opportunities which help the individual to develop its self out of an undifferentiated unconscious; he would have probably prescribed some kind of fugitive experience to quite a number of his patients, if not to 20th century European society at large. I am not oblivious to the important difference between deliberately moving out of one’s comfort zone to explore new physical, intellectual and spiritual horizons and being literally evicted from one’s home, but I agree with Machleidt that we need to change our integration policies and build them on the premise that such experiences harbor an enormous potential for the individual to grow. It is the host society’s job to harvest this potential by taking over the responsibility of a new parent surrogate, which provides not only shelter but also structure and limitations.

Most of the men I saw though in that room would have been classified between stage 2 and 5: none of them was forcefully pushed out of his chosen habitat. Nevertheless, there were severe differences between single employees of large MNOs who played with the thought of leaving China because of air pollution (stage 8.5 need) and obnoxious superiors (stage 6 need) and would be able to get a safe and well paid job in some other unit of the same company back in Europe; and a single entrepreneur who on top of all other consideration seriously considers to pack up his family after a failed start up and to move forward into an uncertain and undecided future of unknown location and vocation. Personal conditions look different from inside out. They surely do, but I was wondering why some of the participants had to strengthen their faith considering their snug and fat lives. My guess is that status and reputation plays at a certain stage in our lives an exponentially important role aggravating our doubt over the future and its challenges. If you have nothing, there is nothing to loose, but if you have something, our quest for security and conformity to preserve what we have, deprives us from being and growing even further. So we start to doubt. Fromm was indeed a smart motherfucker. Conformity is, without doubt, the surest path to mediocrity, boredom and depression.

It was then not surprising that a look at the probably most industrialized and capitalized society on this planet, the United States, reveals that suicide rates are particularly high amongst white Caucasian males. The US Center for Disease Control and Prevention published in April 2016 the report of a long term study of suicide. It states that in 2014, the age-adjusted rate for males (20.7) was more than three times that for females (5.8). The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention claims that 7 out of 10 suicides in 2014 were committed by white men. One can not help but to be reminded of the 2010 movie Company Men, which shows how the self-esteem movement paired with a capitalist system drives in particular white middle aged men into marginalization and depression.

Suicide is only the tip of an iceberg of mental illness, but in my understanding the most important indicator of a culture’s sanity. Beneath, much less visible are stress, burn out syndrome, alcohol and drug abuse, paranoia, psychosis and the epidemic of gnawing self doubt. The doubt of the self translates directly into a lack of faith in God, because after all, God is not some mythical creature, but a force that lives within each one of us; whether we are conscious of that force or not is irrelevant. A few months ago I read at the door of the Rudolf Steiner library in Switzerland a quote of the Baroque physician and poet Angelus Silesius, which perfectly describes how this self doubt is identical with lack of faith:

Behold, where are you bound? Heaven is within.

Searching God without, again and again you’re missing him.

The disability activist Caroline Casey talks about her very personal story of finding that freedom within. Being legally blind since birth, but only finding out at age 17, she fights her disability until she has a breakdown at age 28 in her then position as global management consultant at Accenture. The philosopher Eckhart Tolle writes in A New Earth, that people with heavy pain-bodies usually have a better chance to awaken spiritually than those with a relatively light one. Whereas some of them do remain trapped in their heavy pain-bodies, many others reach a point where they cannot live with their unhappiness any longer, and so their motivation to awaken becomes strong. Pretending to see in a predominantly visual world must have been a daily pain beyond measure fore Caroline. But most of us suffer only from average pain and are thus trapped by the psychology of group pressure within capitalist consumer societies. We go with the flow, because it takes too much effort to move out of our comfort zones and might on top of that sever some of our closest relationships.

Transformation and Suffering.

My natural resentment against Australia’s pleasure culture helped me to understand first hand what psychologist Seligman meant with the destructive force of the self-esteem movement, when he wrote 1990 that in the 1960s the emblematic children’s book was The Little Engine That Could. It is about doing well in the world, about persisting and therefore overcoming obstacles. Now many children’s books are about feeling good, having high self-esteem, and exuding confidence. Australia is all about that and I felt as if Australian’s at large – individual exceptions put aside – are a nation in narcissistic regression to satisfy these needs of the self; they lack identification figures of what constitutes a mature adult, someone who cares about more than himself like the local community, domesticated and wild life stock or how individual decisions impact the global environment; simply somebody who acts responsibly and is willing to put himself in second place.

It would be interesting to analyze in depth how the self esteem movement transformed the original story of The Little Engine That Could into the Starlight Express, where instead of one engine fighting against himself to overcome interior obstacles, various engines compete to become the fastest engine in the world. One reason is without question based on Rev W. Awdry's refusal to give Andrew Lloyd Webber permission to us the characters of his Railway Series books for a musical adaptation. But a deeper and probably less known reason is to be found in our collective unconscious which underwent a massive transformation - starting with the rise of postmodernism of the 1960s - from individuals striving for the greater good by cooperating in unity to individuals striving for their own good by competing against each other.

Australia also helped me to understand what Frankl wrote 1984 about the three main avenues on which one arrives at meaning in life. He said that the first is by creating a work or by doing a deed; the second is by experiencing something or encountering someone; in other words, meaning can be found not only in work but also in love. Most important, however, is the third avenue to meaning in life: even the helpless victim of a hopeless situation, facing a fate he cannot change, may rise above himself, may grow beyond himself, and by so doing change himself. He may turn a personal tragedy into a triumph. Frankl’s main proponent in the US, Edith Weisskopf-Joelson, expressed hope that logotherapy may help to counteract certain unhealthy trends in the present-day culture of the United States, where the incurable sufferer is given very little opportunity to be proud of his suffering and to consider it ennobling rather than degrading so that he is not only unhappy, but also ashamed of being unhappy.

With reference to earlier elaborations on rising suicide rates, widespread depression, pandemic boredom and other mental health issues like burnout syndrome or ADHD in affluent societies, it seems as if we are meant to diverge some traffic to that third avenue on which one arrives at meaning in life. Suffering has lost its appeal since WWII and people don’t want to suffer, they push suffering away and instead of facing it, they engage in a plethora of compensation behaviors from shopping sprees to drug abuse. I feel though that it is a safe vehicle to not only personal growth but also to personal transformation, because it is through the gates of suffering that we enter fast forward the realm of compassion and kindness.

Transformation and Compassion.

If you would ask me about my religious inclinations, I would tell you that I consider myself a Taoist with strong Buddhist features who sees lots of value in adhering to some if not too much Confucian structures in everyday life. Its exactly in my religious outlook that I am more Chinese than most of my chosen fellow country man. But it shall be explained to the reader who does not share my interest in religion and spirituality, that none of these three schools of thought are in a narrow definition a religion, i.e. a concept which teaches the existence of a superhuman all powerful being which is separated from us, but rather philosophies which teach the human being how to live better and more harmonious lives. Interestingly, I have found recently a layer in my identity which is clearly is Christian, but I had to first understand the central role of compassion through Buddhism, to realize that it is also Christianity’s central message wrapped into lots of unattractive suffering.

How much more was I able to relate to a prince who felt suffering in this world and turned into a saint by recognizing how to master his mind and open his heart without being stoned by angry Jews and nailed to a wooden cross. How much more could I relate to Buddhism as a school of thought, an ancient form of positive psychology which reduces suffering, than to a carpenter’s son whose blood stained groin cloth turned into a flag for crusades, inquisition and an increase of suffering. Yet another piece in the puzzle of Christianity fell in place during this year’s Hong Kong retreat under the title “Faith and Doubt”.

What does it mean to be Christian? Let me start with a negative definition: Being a Christian is not related to exterior realities like the condition of the church or the behavior of its officials. And let me follow up with a positive definition: Being a Christian means to genuinely love your neighbor, to not judge him based on prejudice, but to guide him onto the path of purification and reformation to God’s infinite love. All those who have turned their back upon Christianity during the last decades were – like myself – enthralled in an exterior reality with which they were not anymore able to identify themselves with. But the genuine Christian perceives his connection to God as an inner reality, which he lives through his love of the fellow human being in every moment of thought, word and deed.

Christ and Buddha arrived at the same conclusion which can be understood as the very bottom line of their teachings: God is a reality which we can most clearly perceive through compassion with our fellow human beings, which reduces suffering. Christianity has enshrined this insight in the second great commandment: Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself. But it is Buddhism, which teaches a more refined concept of Karuṇā (compassion) being one of four attitudes learned on man’s spiritual path towards enlightenment. The other three are loving kindness (Pāli: mettā), sympathetic joy (mudita) and equanimity (upekkha). I still struggle to understand why these fundamental and simple insights have been perverted by power driven institutions into complex and repulsive doctrines.

Transformation and Lent.

Miriam Webster’s dictionary defines Lent (in the Christian Church) as the period preceding Easter, which is devoted to fasting, abstinence, and penitence in commemoration of Christ's fasting in the wilderness. In the Western Church it runs from Ash Wednesday to Holy Saturday, and so includes forty weekdays. In March 2017 I at Bishop Lei’s Hotel in Hong Kong and read from the screens these lines about Lent:

Lent is the road leading from slavery to freedom, from suffering to joy, from death to life. Lent is the time for saying no. No to the spiritual asphyxia born out of the pollution caused by indifference, by thinking that other's people's lives are not my concern. Lent is the time to make room in our life for all the good things that we are able to do. Lent is the time of remembering what we would be if God had closed his doors on us. Lent is the time to start breathing again. it is the time of turning through the breath of God our dust into humanity. Lent is the time of compassion. It is the time to set aside everything that isolates, enclosed and paralyzes us. Lent is a path: it leads to the triumph of mercy over all that would crush us or reduce us to something not worthy of the dignity to be called God's children.

These lines and my deliberate choice to refrain from alcohol, sugar, nicotine and other drugs for the duration of lent made me understand why Christianity wraps its central teaching of compassion into a thick layer of suffering. Its because suffering helps us to grow beyond imagination; the pain of the sufferer is the only road sign required on our path; and it is a road sign which we put up ourselves. If we do not volunteer to suffer, to deprive ourselves from behaviors, things and people we have grown accustomed to, we fail to grow and fail to realize our potential. Lent is an opportunity to volunteer.

Life is a journey, a migration, a transformation towards God. It's a journey which leads inside not outside or rather our external conditions in the material world reflect our inner conditions in the spiritual world. Time is the subjective reality on which we travel, in permanently self destructive mode, we shorten our lifespan suffering, in consistent creative mode we extend it, enjoying ourselves in shining for others. But without the possibility to suffer properly we are deprived of making leaps of enlightenment propelled by the pain of sudden realizations and are dragged into a swamp like Pachinko mode of amusing ourselves to death.

Some time ago I published an essay on LinkedIn titled Why I Want to Leave China and Why I Don't, which I had written back in 2014, then convincing myself to stay in this rollercoaster country. It was quite well received and shortly afterwards, I got an email by an acquaintance containing a peculiar differentiation of man which I want to share here in all brevity.

There are three main reasons for everyone to be somewhere: 1. You are here because you are born here, the majority of your family lives here, you own some land or house here, and therefore you have a solid legitimate reason to be here no matter what your political instincts, religious tendencies or sexual interests are. Let’s call them H(ome) guys 2. You came here in search for a new opportunity, disguised as adventure, love affair, search for gold or money or cultural novelty. Let’s call them S(earch) guys 3. You didn’t want to be here, but you had to flee from something, somebody or somewhere and you just stranded here, and you anyhow didn’t know where to go exactly. Let’s call them F(light) guys.

The mail continues that most places are quite a mixture of these 3 groups, but the composition varies greatly and makes a huge difference to the general attitude of the local society. Shanghai’s majority belongs to the S group, followed by H and no visible F group. European cities differ tremendously with a way higher H group and a perceived huge F group. I don’t know why but one’s comfort is increased if you belong the biggest group, so in Shanghai you definitely find it initially exciting to be part of a huge S group. But S people leaving, you wonder if you will eventually become a member of the H group, but it doesn’t take long to realize that this will not happen in your generation, probably though in the next; but if this we don’t know.

The above differentiation makes a lot of sense, and I largely agree with the author, but it lacks a very important perspective, because it describes only the reasons for our whereabouts in the physical world and takes this description as its foundation to explain our choice of location. I have come to the conclusion that, yes, many people put considerations within the physical world above everything, but in the last extent it is our outlook on in the spiritual realm which defines where we are and were head to. I therefore differentiate nowadays two sort of people: those who have found a spiritual home, no matter where they are and what they do; and those who have not. The Jesuit paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin formulated this perception cogently as such: The Marxist contradiction between worker and capitalist is obsolete; its not a class struggle, but the spirit of evolution, which separates humanity into two parties. Here are these who perceive our planet as a comfy living room; and there are those who perceive Earth as a developing organism. Here the spirit of Bourgeoisie, there mankind’s actual proletarians.

These proletarians or migrant workers, as I call them, can belong to the above mentioned H and F group. They might have stable families, own posh houses and devote years of effort to building communities and sharing values. They might nevertheless at certain stages in their lives be classified as member of the flight group, in particular during the years which Jung attributed to the process of individuation. Peeling off cultural conditioning and developing a true self often involves physical detachment from one’s originating society. That’s why Mark Twain wrote early in the 20th century about his fellow US country men: Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one's lifetime. These migrant workers never belong though to the ever growing S group which tries to find something in the material realm that can only be found in the spiritual and from there be mirrored into our daily lives.

I have myself always differentiated amongst foreigners in China between culture nerds, spiritual mystics and economic opportunist and have noticed that since the WFC the latter form a clear and increasing majority; but I have to concede that there are many more migrant workers amongst all three of these groups than I would find in a comparable sample back home. Most of these people move out of their comfort zone and strive for a new horizon. When I look at those who return to their originating societies or move on from China to another country, I see that all these rather rigid categorizations can’t encompass the reality of a human life which is always – if one permits - in transformation. I believe therefore that all categorizations must be read in the light of human development psychology, in particular Erickson’s stages of psychosocial development which I explained last year and Loevinger’s stages of ego development.

When my wife and me discuss lately reasons for leaving China top results are related to our children. Their socialization and exposure to my native culture; a better and better value education; interaction with “green” nature. But we, too, have a desire to simplify our lives and leave despite its convenience this stressful urban environment.

If one is not predestined to move on to a place where relatives or second homes have to be taken care of, I have noticed that the decision process can turn for some into a real odyssey. A friend of mine made a list with 140 different items which are important to him and his family respectively, including as simple items as sausages he likes to eat and beer brands he likes to drink, as well as more complex items like schools with specific curricula or certain health insurance schemes. He then weighted the items and evaluated on basis of that list several destinations. This rationally engineered decision process, which reminded me very much of data strategist Amy Webb, who did the same thing for finding her husband, helped him to pick the top scoring country and move there. Evaluation pending.

Another friend of mine collects since a substantial while data on potential destinations, where properly researched and crowd sourced information about costs of daily living, taxation, visa and financial requirements, health care, safety, education, environment, climate, political and social stability et cetera is maintained. He shared with me a few of the websites[i] which are being used by a growing species of global nomads; all of them most likely to be categorized firstly, S and secondly, Bourgeois; and a minority which truly wants to grow but can’t find the resources for this growth within and thus follows life style design idols like Tim Ferris, who perceive the planet as a global playground and their life as a vessel to be filled with excitement. This friend’s decision is still pending.

Transformation and Transformer.

My two friends prompted me to question the necessity to make such lists or mine for respective data, because it felt like the infamous search for the needle in a haystack. What if there was another, easier though not less sophisticated path to firstly, recognize the right timing for a transformation and secondly, the right destination. What if I could spare myself all the ruminations about where to go and what to do and save myself the tedious time of comparing online data? And would all this rationalized information lead to any good result? If I am lucky it can, but I wouldn’t count on it.

The culture critic Neil Postman argued in 1990 – what would he say as of 2017? - that our society relies too heavily on information to fix our problems, especially the fundamental problems of human philosophy and survival, that information, ever since the printing press, has become a burden and garbage instead of a rare blessing […] what started out as a liberating stream has turned into a deluge of chaos […] matters have reached such proportions today that for the average person, information no longer has any relation to the solution of problems […] Information is now a commodity that can be bought and sold, or used as a form of entertainment, or worn like a garment to enhance one's status. It comes indiscriminately, directed at no one in particular, disconnected from usefulness; we are glutted with information, drowning in information, have no control over it, don't know what to do with it […] the tie between information and action has been severed.

I believe that in an era of digital deluge more and more people feel overwhelmed by both the information and the life style choices available; I at least did until not too long ago. It came as a timely relief to listen to two talks on our 2016 Hong Kong retreat, which made me drop Six Sigma change management and instilled a new attitude towards the uncertainty coming. One speaker elaborated on his understanding of sin and differentiated between mortal sin, i.e. something evil being done on purpose, and general sin, i.e. not being receptive for God’s signal. He compared living in general sin with a TV program which can’t be watched due to interference and asked how we can tune our TV reception for a clear divine transmission. I was surprised to hear such an analogy in a Christian setting, but found clear parallels to Taoist and Buddist teaching which answers that question with atonement exercises, that is e.g. taichi and meditation. After all it is the search inside which brings salvation or as the Chinese say: 回头是岸。

One could add in the financial times we live in yet the economic perspective, which was described by Adam Smith as the invisible hand, i.e. his notion that individuals' efforts to pursue their own interests may frequently benefit society more than if their actions were directly intending to benefit society. The father of capitalism sanctifying self-love over selfishness as a law inherent to economy.

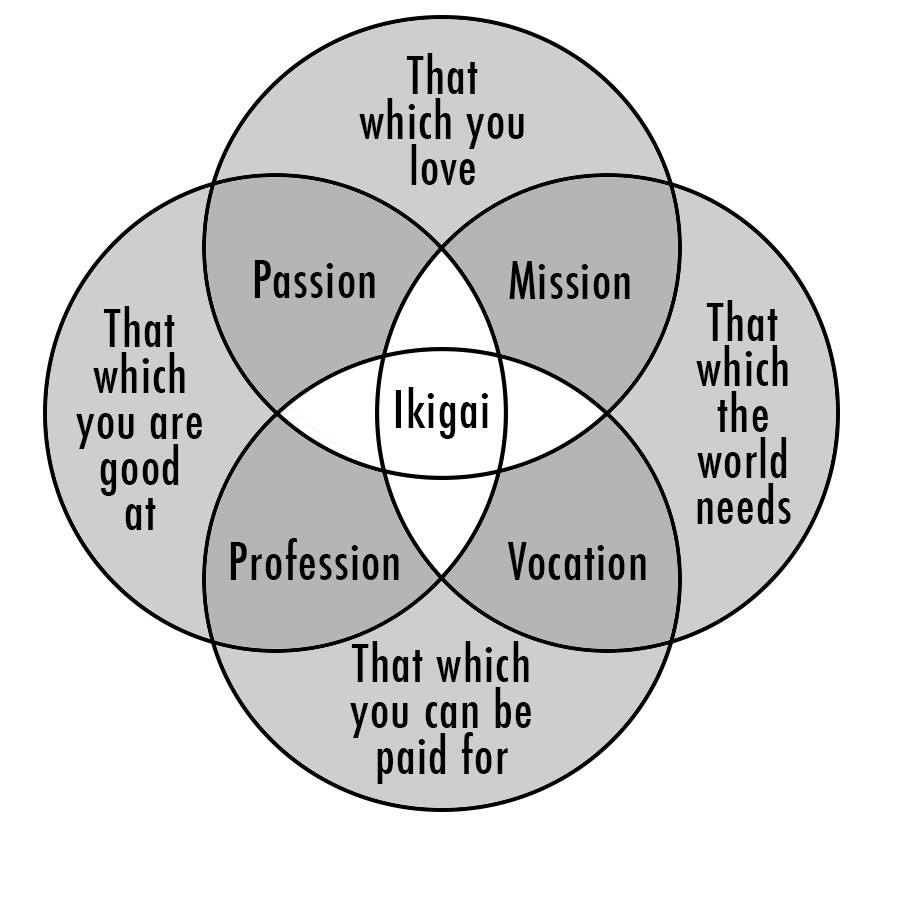

What I took though from both talks was a reference to God being the transformer who makes the neurotic hoarding of information obsolete because he transmits his message to those who listen in the required moment and probably more importantly with better knowledge of our needs and the needs of the world than ourselves. The talks made me yet again think of the Japanese concept of ikigai, which I found in a beautiful diagram which I couldn’t make sense of rationally. But it made perfect sense once I recalled the Zen paradigm of a student asking his master: How do I attain Zen? The master answers: Pour me some more tea and I will show you. But master, the disciple replies, your cup is already full. Just do it, the master urges him. The disciple does as he is told, and the brew spills all over the table. In this moment the student attains Zen as he realizes that in order to become enlightened his mind must be empty. The same is true for wisdom, i.e. making the right decisions in the right moment. If both our cerebral as well as our gastric convolutions are congested with information garbage and junk food, it is no surprise that we can’t receive a strong signal.

Another friend told me not too long ago, that even if we receive a strong signal, we confine ourselves to a small purpose because we are afraid of the purpose God assigns to us; and rightly so, he says: see, what e.g. Jesus got from fulfilling his duty. Our fear of death is ultimately in our own way. He is probably right, because the fear of death is surely underneath all our fears; but who says that God wants you to be stoned and crucified? It is this outlook on life which Christianity popularized; but it is our tendency to get entrenched in avoidable suffering, and the narcissistic self-esteem movement which negates the ability to bear real suffering that makes it so difficult to grow towards self-love and towards God simultaneously.

Nelson Mandela, who sat for years in prison confinement could have probably just hanged himself or giving up upon him like many of Viktor Frankl’s concentration camp inmates did, but he never lost his hope, lived till age 95 and produced these deeply moving words instead, which clearly show that beyond our fears there hides teleological transformation, i.e. clear direction and guidance which comes from deep within.

Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure. It is our light, not our darkness that most frightens us. We ask ourselves, Who am I to be brilliant, gorgeous, talented, fabulous? Actually, who are you not to be? You are a child of God. Your playing small does not serve the world. There is nothing enlightened about shrinking so that other people won't feel Your playing small does not serve the world. There is nothing enlightened about shrinking so that other people won't feel insecure around you. anifest the glory of God that is within us. It's not just in some of us; it's in everyone. And as we let our own light shine, we unconsciously give other people permission to do the same. As we are liberated from our own fear, our presence automatically liberates others.

Franz Kafka on the other hand, the early 20th century prodigy writer, who produced beautifully crafted works like The Process and The Castle, lost all hope. His spiritual and physical decay is left to us as part of his literary legacy in The Metamorphosis; the novella portrays in my humble opinion Kafka’s own dreams of being transformed from man to insect; recurring nightmares of a highly sensitive person, who stayed in the self chosen confinements of a legal day job with a Prague based insurer, instead of growing towards the light and transforming into something better, e.g. using his wordsmithing talents to convey the message of light instead of darkness to his readership. Kafka died at age 40 from tuberculosis.

The legendary Taoist philosopher Zhuangzi whom we know from his parable of comparing man with a butterfly described this metamorphosis from outside in rather than from inside out: When people are asleep, their spirits wander off; when they are awake, their bodies are like an open door, so that everything they touch becomes an entanglement. Day after day they use their minds to stir up trouble; they become boastful, sneaky, secretive. They are consumed with anxiety over trivial matters but remain arrogantly oblivious to the things truly worth fearing. Their words fly from their mouths like crossbow bolts, so sure are they that they know right from wrong. They cling to their positions as though they had sworn an oath, so sure are they of victory. Their gradual decline is like autumn fading into winter – this is how they dwindle day by day. They drown in what they do – you cannot make them turn back. They begin to suffocate, as though sealed up in a box – this is how they decline into senility. And as their minds approach death, nothing can cause them to turn back toward the light.