| 181018_film_review_-_lo_and_behold.pdf |

Leonard Kleinrock, one of the internet pioneers who sent the first message from UCLA to Stanford explains to Herzog that it was intended to type log into the UCLA interface as in log in, but the connection broke down after the second letter was transmitted, resulting in an enigmatic or accidental lo. It is only from this perspective that the film can be understood in its entire depth which over and again touches on questions of religion, spirituality and consciousness.

The room from where the first message was sent at UCLA on the evening of October 29, 1969, is described by Kleinrock as a sacred place, a temple of divine history and as a shrine of immaculate birth. Herzog seems to explore for the next 90 minutes if this God born under the auspices of a few wise man at two ivory league North American universities is what theologians call the second coming or a wicked manifestation of the anti-Christ; and by doing so, he reflects on what a significant number of cutting edge technology thinkers crunch their minds on in recent years. The internet, precursor, enabler and embodiment of cyber physical systems is the Alpha of an Omega which a few welcome, but many fear: singularity.

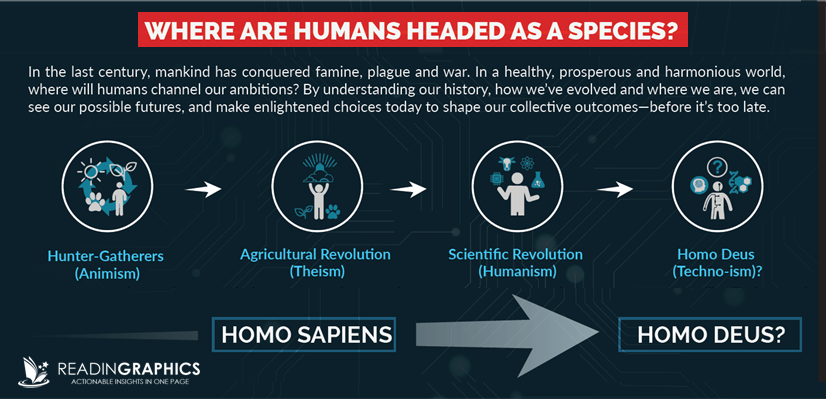

If Peter Joseph, the director of the Zeitgeist trilogy, says somewhat in line with Thrun’s vision that human employment is in direct competition with automation, then George Bernhard Shaw would probably answer to both of them: The biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place. Why? Let’s think exponential technological change to the very end and assume that technology is per se evil or that it is the evil in man which turns the creation against its creator. There won’t be any competition. There will be only extermination and no attempt at teaching humans more and making them capable of learning faster will be of avail. What we need is less intelligence and more wisdom.

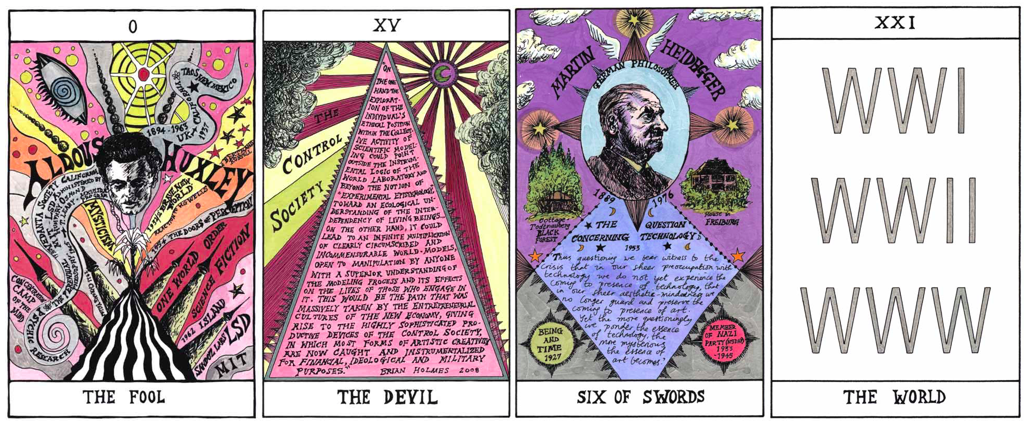

Realist philosopher Martin Heidegger emphasized the ambiguity of technology in his 1954 treatise The Question Concerning Technology. While Dyson’s definition of technology would be labelled by Heidegger as bringing-forth, most of modern technology, including many of the applications of the internet are a challenging-forth, i.e. the (ab)use of technology by corporate or government power structures. Heidegger describes this threat with the term enframing and means thereby the subjection of technology to means which do serve a man controlled end.

The brutal destruction of WWII influenced Heidegger like many other of his contemporaries. Aldous Huxley e.g. wrote in 1957 On the Politics of Ecology, where he describes that the science-technology-power complex enframes our human societies. Both men are part of a set of tarot cards created by artist Suzanne Treister which decorates since five years as magnified prints our dining room. The devil in this set of cards is the control society, a society which philosopher Sir Karl Popper described as tyranny and which he juxtaposed to democracy. Treister doesn’t seem to agree with Popper and thinks of the internet as the continuation of the two world wars, which turns democracies into tyrannies. Enframed technology brings nothing forth, it only challenges-forth.

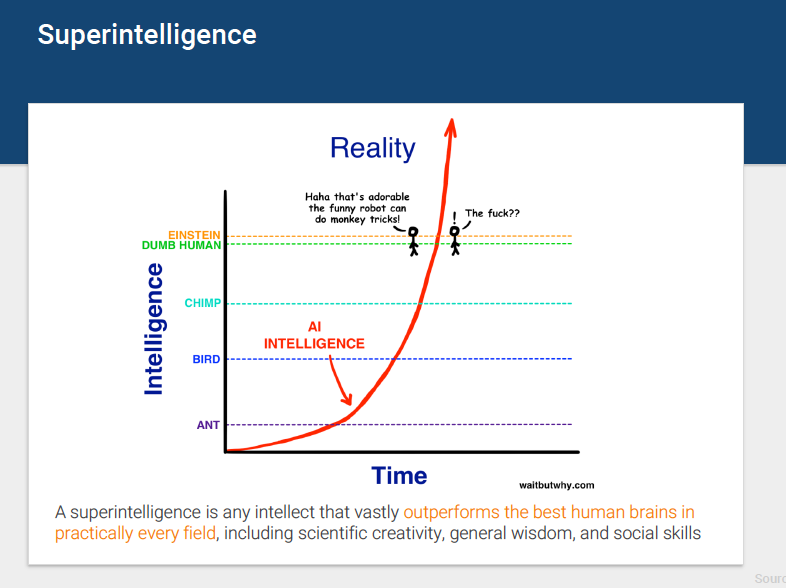

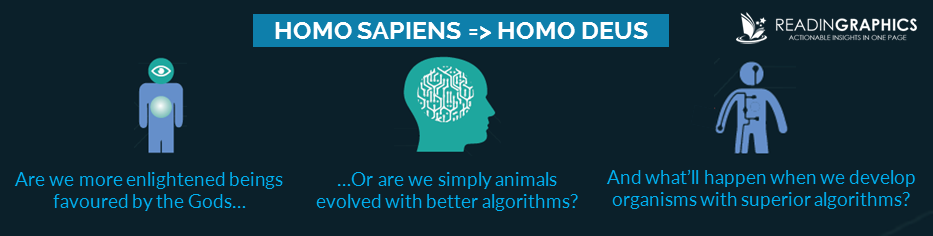

Herzog dedicates the last section of his film to a rather cryptic question which he asks not only Musk but also scientists in various disciplines: Does the internet dream of itself? He implies that the internet has already started to develop self-awareness on its way to become an almighty superintelligence. Are those dreams subject to the Law of Large Numbers as computer scientist Kleinrock explains in the beginning of the documentary? A large number of unpredictable players or messengers collectively behave in a very predictable fashion, a fashion which we can write down exactly and we therefore can predict the performance of a network when its large. Does the internet dream the sum of what most of us dream or is it detached from humanity and dreams on its own? And is the role of the human being one that can be substituted by artificial intelligence or is ours essentially to dream up the future, while algorithms will make it happen?

The author of The Neverending Story, Michael Ende, envisioned in the still early years of television, the first screen which our species got hooked on, a world with children who lose their ability to dream, because they stop reading books. It is this collective loss which translates in the story into a spreading darkness devouring Fantasia, the land of dreams with all its fantastic creatures. Does the internet indeed destroy our dreams? I wouldn’t know. Technology writer Nicolas Carr and many others like educator and culture critic Neil Postman before him are convinced that we lose our ability to think deeply and critically and thus become shallow human beings; too shallow to be able to pursue truth.

It is as if badly designed technological progress engulfs our minds and spirits with a coat of smudge. It is as if technology brings about a renaissance of the dark medieval ages. Then it was the ideological control which in particular the Holy Roman Church and Fareast Asian Confucianism wielded over human thinking. Now it is the technological control which almighty corporations and regimes exert over their customers and subjects. Both limit man’s ability to connect with the spiritual realm. The church confined man to the scholastic interpretation of existing information. The Lords of the internet confine man to regurgitate the noise of its echo chambers.

In the Internet age, Henry Kissinger writes, world order has often been equated with the proposition that if people have the ability to freely know and exchange the world’s information, the natural human drive toward freedom will take root and fulfill itself, and history will run on autopilot, as it were. But philosophers and poets have long separated the mind’s purview into three components: information, knowledge, and wisdom.

The Internet focuses on the realm of information, whose spread it facilitates exponentially. Ever more complex functions are devised, particularly capable of responding to questions of fact, which are not themselves altered by the passage of time. Search engines are able to handle increasing speed. Yet a surfeit of information may paradoxically inhibit the acquisition of knowledge and push wisdom even further away than it was before. Communication technology threatens to diminish the individual’s capacity for an inward quest by increasing his reliance on technology as a facilitator and mediator of thought. The poet T. S. Eliot captured this in his “Choruses from ‘The Rock’”:

Where is the Life we have lost in living?

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?

How do we learn to dream? How to we learn to take care of each other? Certainly not by spending long hours playing video games. Certainly not by being tied into an internet consumption matrix. We need to find means and ways to reconnect with each other and the planet. Neurologist Allan Schore has written extensively on right hemisphere interactions between child and caretaker and their importance for psychopathology, and there is growing evidence that attachment and failures in attachment between mother and child affect autonomic, neurochemical, and hormonal functions in a growing brain. Neurologist Mirella Dapretto describes the necessity of strong caretake and child relationships in a similar way: Typically developing children can rely on a right hemisphere mirroring neural mechanism – interfacing with the limbic system via the insula – whereby the meaning of the imitated (or observed) emotion is directly felt and hence understood.

The neurological effects of disrupted early childhood relationships as explained by Schore and Daretto have serious implications for increasingly individualized societies: they condition us for adult life and define how our societies work at large. We do not only grow up in family systems which have shrunk from transgenerational to nuclear entities, i.e. from ten and more people to three or only a single parent with a child; we have moreover completely changed the way we interact with each other compared to only a generation ago. Siri Hustvedt wrote in one of her essays that philosopher Martin Buber was right when he said that psychological illnesses do grow up in between people. I agree with her.

- Martin Heidegger: The Question Concerning Technology

- Aldous Huxley: The Politics of Ecology

- Lukas Makuch explaining machine learning, deep learning and AI

- Will Schroder on How to remember everything you learn

- Nicolas Carr about his book The Shallows

- The Tech Insiders Who Fear a Smartphone Dystopia

- Inside the Rehab Saving Young Men from their Internet Addiction

- As Addictive as Gardening: How dangerous is video gaming?

- Irresistible: Why you are addicted to technology and how to set yourself free by Adam Alter

- Allan Schore, Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self: The Neurobiology of Emotional Development (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1994)

- Mirella Depretto et al., Understanding Emotions in Others: Mirror Neuron Dysfunction in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (Nature Neuroscience, 2006: 28-30)