Three days of depression, lethargy and atrophy follow. I lie around like a slug. Our son irritates me with every word he says, with every move he makes. I just want to stay put in a place, hide in a cave, an earth mound would be best, I figure. Eventually, I just drop my carcass on the beach next to our hotel, watch our son enjoying himself in the waves, my brother playing with him. I start to worry. Have I developed multiple sclerosis or am I about to die for some unknown reason? Should I after all quit my vegetarian diet? Would meat give me the energy to keep going? Would I actually want to keep going? I seem to lack any intrinsic motivation to do so.

My stamina slowly returns after a few motionless hours as if my body lying on the beach is charged by being in full contact with mother Earth. Have I depleted my batteries to this level of exhaustion in only four months? Is this what the technocrat-capitalist system does to human beings? Or is this the result of urban alienation and Shanghai’s accelerated pace of life? Is it me working too many hours on too many different projects? All of it? Probably I am just getting old and need to manage my time and energy better; but I feel like this is a sort of a bodymind awakening. My body unwilling to engage in mind-numbing gym exercises to keep fit for the city life; lately even rejecting Mark Lauren’s time saving fitness app which helped me avoid the gym and its crowd. My mind is in permanent dreaming mode visualizing me ploughing every day a few hours in a fruit and veggie orchard burning my calories by engaging in diverse and purposeful work.

Monty Python’s Ministry of Silly Walks should conduct interdisciplinary research based on psychologist Robert Wiseman’s 2007 report that the world’s walking pace accelerated by 10% since the 90s; and probably another 10% since that report. Most likely health advice: walk silly instead of fast. I still remember when my lawyer friend Markus told me back in 2007 that New Yorkers walk at 6.6 km/h while Viennese average at 5.5 km/h. He then suggested that faster is better, that speed indicates progress. I instinctively knew then that Markus was wrong, but kept speeding up myself in a personal race for modernization, wealth acquisition and trying to make sense of a life within the capitalist system. A decade later, I am so accelerated by modern communication forms that I can’t slow down any more even if my body is failing me.

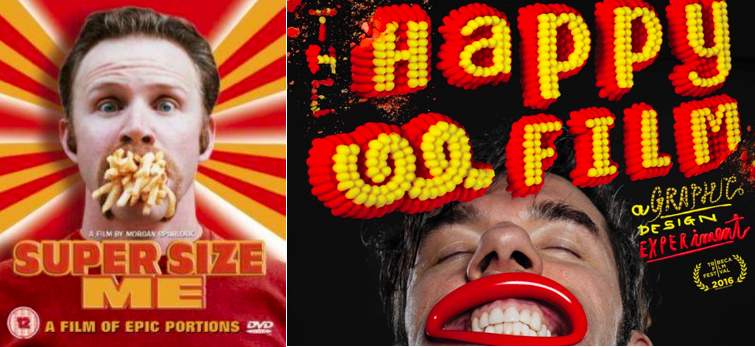

It’s probably not a coincidence that we watch Stefan Sagmeister’s Happy Film and Steve Conrad’s The Pursuit of Happyness within only 24 hours. Both movies are obviously about happiness, but while I feel absolutely miserable, I realize that they each put a very small spotlight on this vast and obscure subject: one looks at intrinsic factors only, the other mainly on extrinsic conditions. Let’s take the opportunity of my brother treating himself to a 90 minutes Thai massage and our son having fallen into a comatose nap to look into both movies a bit deeper.

Ever since I have watched Sagmeister’s TED talk The Power of Time Off, I felt that this fellow has something to say and the talent to present what he says in a visually captivating form. The film is though disturbing in many ways and Sagmeister realizes that it portrays himself as an asshole and emotional retard. What he has shown most obviously though is that he can’t take time off. He is one of those people, like myself, who are always busy, even if they pretend to close down shop for an entire year.

He went in his sabbatical to Bali and filled his creative well with many ideas; I stayed in Shanghai for mine and filled my entrepreneurial well with multiple projects – instead of taking time off to slow down and think about what really matters. Sagmeister calls New York his home, I do Shanghai. We both suffer from urban alienation and probably some more serious issues in terms of personal history; but I don’t want to draw too many parallels. Here are the main differences: Sagmeister is a prolific executioner, driven by a turbo charged top-down focus realizing one creative project after another; and he does look like most psychologist only into what makes the individual intrinsically happy. I am a lousy executive driven by a broad bottom-up focus and I look much more at individual well-being as an integral part of the collective and as such at extrinsic causes.

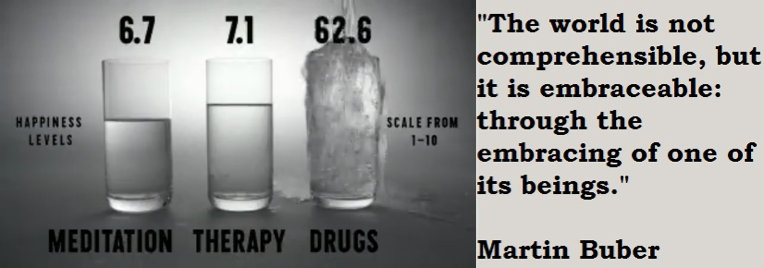

All three methods try happiness stimulation from within, instead of taking responsibility to change what stimulates us from without, i.e. culture at large. While Sagmeister is one of those few people who thrive in a highly competitive and extrovert capitalist system, there is another story to tell about happiness, which is more of the sort what Barbara Ehrenreich described in Smile or Die: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking Has Undermined America.

Sagmeister is a professional exhibitionist, turning the most intimate about himself outside; and he is a master of the visual medium, and as such the medium which dominates the linear economy increasingly since WWI through advertising. He does not only sustain the current economic system, he is like a demon who has helped to grow it into what it is today: a heaven for a few and a nightmare for most. Promoting the idea that happiness is within your grasp is in the interests of corporations trying to bamboozle an overworked and underpaid workforce. Sagmeister collaborates with those corporations to sell products which people buy to compensate their alienation. He is the high priest of a religion of sensory stimulation persuading consumers to buy what they don’t need.

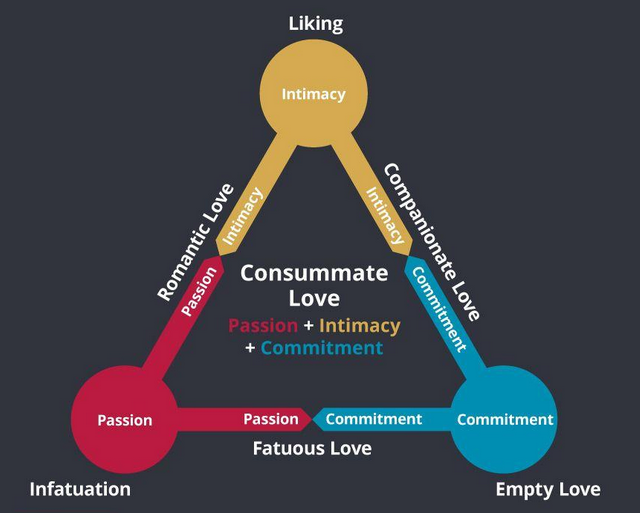

His scientific advisor, social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, author of The Happiness Hypothesis, tells him already early into the film that happiness is not the result of getting what we want; neither is its source solely within us like Buddhists and Stoics seem to teach. How often have I heard lately 做更好的自己 | be a better self? But for whom? Be a better self for yourself? Happiness is according to Haidt rather rooted in relationships between the self and others, to one’s work and to something larger than oneself. Despite being pointed into the right direction, Sagmeister does not heed the academic advice and produces a movie which shows him, the high priest of capitalist advertising, in trying to get what he wants.

Without having read Haidt’s work, it is obvious that his research conclusion refers to Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy, which he formulated in the classic concentration camp memoir Man’s Search for Meaning: For success, like happiness, cannot be pursued; it must ensue, as personal dedication to a cause greater than oneself or as the by-product of one’s surrender to a person other than oneself. Happiness must happen, and the same holds for success: you have to let it happen by not caring about it.

Sagmeister did probably not care about success, but clearly cares too much about happiness and he fails in all his attempts to attain happiness by not surrendering himself to something larger then oneself. Individualist meditation camps clearly attract people who don’t give back to society, but want to pull themselves out of misery by chanting happiness mantras instead of doing the work; narcissist therapy sessions with star psychologist Sheenah Hankin in a posh Upper East Side practice neither seem to be a choice of deliberately subjecting oneself to a cause greater than oneself, but are rather a brooding over and regurgitation of one’s own small universe; and seeing psychopharmcologist Tony Ocampo for a Lexapro prescription is surely the last resort of someone who is incapable of finding a purpose outside his small universe. Taking psychochemical drugs is in many cases - surely in Sagmeister’s - like giving up self-responsibility.

Why didn’t he simply pick a Burmese nonprofit initiative and support its work for a year free of charge? Why didn’t he start a public campaign against the rampant environmental pollution mostly caused by tourism on Bali? Why didn’t he make a documentary about the Mumbai beach cleaning? Wouldn’t there be so many worthy causes to which a man with the talents of Stefan Sagmeister could contribute? About two years ago, I wrote about the causes of the mid-life-crisis and came to the conclusion that it is ultimately the realization of impending death which drives people between 40 and 60 into MLC.

Sagmeister shows in his film that he is a serious MLC case trying to get to terms with the 6th, 7th and 8th social crisis according to Erik Erickson all at once: intimacy, generativity and ego integration. He is in other words stuck on his trajectory of ego development failing to recognize that the causes of happiness are subject to our changing psychological development. What made you happy at age 30 won’t do the job at age 50.

Fisher tells us that these three brain systems aren’t always connected to each other. That’s why you can feel attachment to one partner, be in a romance with another and crave for yet others. She thus implicitly questions monogamous relationships and many other social institutions like the modern nuclear family; and she explicitly warns about the wide spread use of antidepressants. Psychopharmaceutic drugs like Lexapro raise levels of serotonin and thus suppress the dopamine circuit, which is associated with romantic love; they suffocate the sex drive and thus deprive the brain of the chemicals which are associated with attachment.

Its always dangerous to give any long distance diagnosis, but my experience tells me that hyperactive people like Sagmeister compensate low serotonin levels and as a consequence accelerate their lives to such an extent that they can’t commit anymore to people who cruise at normal speed. It’s as if an interstellar spaceship can’t get into the orbit of a space station and fails to dock over and over again. But one can make a conscious decision and commit to a cause greater than oneself, whether it is a person or a project.

That’s essentially the gist of Emily Esfahani-Smith’s talk on why life is not about happiness but meaning. She thereby builds on Frankl’s decade long suicide research: In a position of utter desolation, when man cannot express himself in positive action, when his only achievement may consist in enduring his sufferings in the right way – an honorable way – in such a position man can, through loving contemplation of the image he carries of his beloved, achieve fulfillment. We all do come closer to such a position of utter desolation when we pass our professional zenith and have to face age and eventually death. Sagmeister’s recent controversy about an outdated and obscene joke at the Wellingtion Webstock conference, which he performs since more a decade, confirms that a 55-year-old can’t continue what a he did when he was 40. Sagmeister clearly is in a prolonged social crisis.

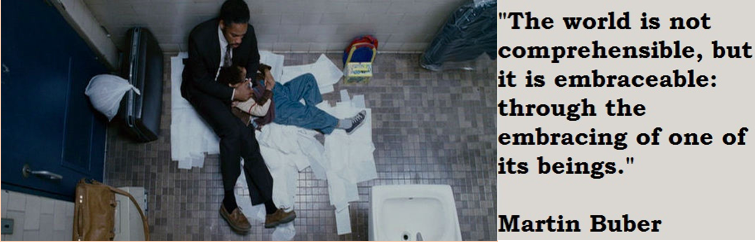

Based on the movie and above thoughts on The Happy Film, I have only two comments to share on Chris Gardner’s story. He certainly did not look for happiness, but tried to solve truly pressing challenges like providing shelter and food; basic amenities which our societies do not give equal access to. In as far this story is not about intrinsic, but about extrinsic factors of happiness, i.e. conditions which are given by a certain society to certain individual members thereof. Barbara Ehrenreich would have more to say about these things and I confirm that extrinsic factors are what we should mostly be talking about in times with widening wealth gaps and the need for a new social contract.

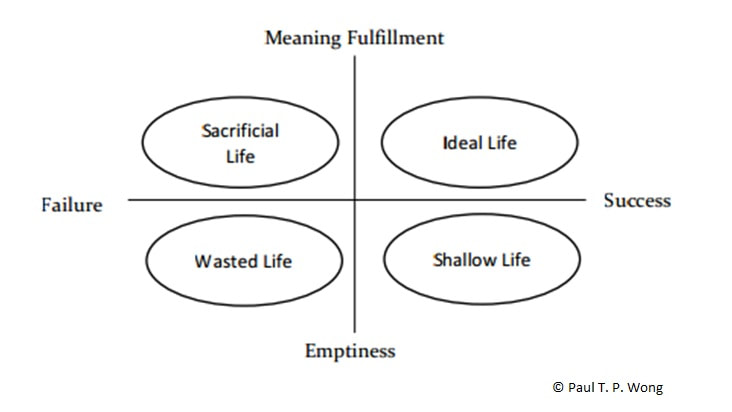

The film gives to certain extent the impression that happiness is related to money only, in particular because Gardner is completely in lack of any financial security and is hardly able to provide for his son. It is though his decision to break with a family history of fathers abandoning their children, that is in the words of Viktor Frankl, by subjecting his own life to his son’s, that he achieves success and happiness without pursuing it. We certainly are in need of a reasonable amount of money in our modern societies, but as Daniel Kahneman explained for the US back in 2009, there is no significant increase in happiness once USD 60k annual income have been exceeded. Comparable numbers do apply to most economies, and Sagmeister is surely far beyond this threshold. He is therefore advised to share and focus on the well-being of others instead of his own ludicrous search for self-stimulation. His life is blessed with professional success, but seems to be empty because he hasn’t found meaning.

All creative undertaking and in particular writing - even the most academic attempt to be objective - is in the one way or other a reflection of the author’s mindset and as such subjective. Sometimes, this subjectivity is only revealed by the chosen subject itself or the title of a work, the pages behind the cover meticulously concealing what the writer was motivated by. I have chosen to write on the pursuit of happiness, urban alienation and the gulag economy, because the subjects are in my recent thinking intrinsically related to one another. Sagmeister’s film and Gardner’s story have triggered this line of thought once more.

I proposed two years ago in the mingong manifesto that humanity’s future is not in cities, but in the countryside. I concede that cities make us more efficient and productive, but they also force us into consumption and convenience, they accelerate life and deprive us of the most important commodity we have: time. We should change our understanding of time fundamentally and apply what Schumacher wrote in Small is Beautiful about natural resources on the time allotted to us: we are estranged from reality and inclined to treat as valueless everything that we have not made ourselves.

Cities are only spheres within a larger system, i.e. our economies. They are the pinnacle of a commodity based capitalism, which ignores natural and human resources. The documentary The Human Scale predicts that in 2050 80% of the world population will live in cities, that is 6.5 billion people. The architects and city planners try to solve the problem of cities which have been planned after WWII for the automobile, by taking back land for people; but they overlook the simple fact that they can’t change the economic system in which cities are embedded by reducing motorways; and they can’t change the fact that cities remain for most of its inhabitants’ consumptive rather than productive spheres.

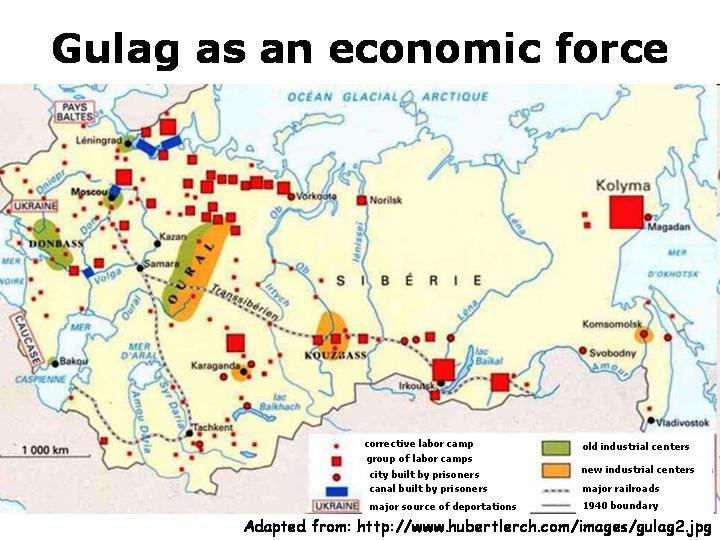

Modern capitalist economies provide to most people the illusion of freedom, but factually enslave them. The popular phrase bluejeans won the cold war indicates that it was the consumer society which won over the totalitarian planning economy. Our global systems have since then converged and we all, whether in Shanghai, New York, Berlin, Cairo or Buenos Aires live in capitalist consumer societies and at least aspiring knowledge economies. Capitalism has somehow succeeded to turn all of humanity into a consumption gulag.

History has shown multiple times that the Confucian zeal of Fareast Asian nations and the capability to imitate and improve has helped them to overtake the West. Japan is apart from the city state Singapore the world’s most urbanized nation with more than 90% of its population dwelling in cities. Korea and China are on similar trajectories; but it is in particular China’s compressed modernization process which pushes people within only two generations from the countryside into urban agglomeration at a pace and a scale never seen before.

What will the implications of such massive social change be? Will we watch in a few years Chinese documentaries like Richard Linklater’s Slacker showing Chinese urban teens and tweens drifting through life without goal nor meaning? Or will Chinese patriotic education as Lenora Chu writes in Little Soldiers keep the nation on track? And if yes, with what objective? It nationalism meaningful?

Linklater’s 1991 experimental film shows young American adult who drift through life without a goal. They lack motivation and stumble from one pleasure seeking to the next; whithout being able to commit to personal relationships nor to project assignments. The psychiatrist Frankl said that man unfolds his potential when he sets an objective and brings maximum tension between himself and that target. It is this missing target and the missing tension between target object and subject which causes all the negativity described in Slacker. It is rather this psychological momentum than what Martin Seligman describes in his 1990 book Learned Optimism as the self-esteem movement and learned helplessness, a term he coined for people who lack grit.

Humanity is today exposed to a collective threat, which paleontologists call the Holocene or sixth mass extinction. Neither Sagmeister’s individualist happiness searching nor Gardner’s parental drive for prosperity seem to be a best practice case for such frame conditions. I have tried throughout the last 18 months to subject my decisions to a safe future for our children. At age 40 I was lucky to let go by my former employer with a paycheck that enabled me to drift and explore for a year what I would like to do next. Whenever a job opportunity opened up, I did consult Viktor Frankl and questioned if such a path was meaningful or just another iteration of my past corporate life. I wanted to spend my second 40 years on this planet for the survival of the next generation, but I have come to a point where I feel that my life has become self-sacrificial and I doubt my decisions.

My own childhood was quite similar to Gardner’s son in The Pursuit of Happiness. My father raised me as a single parent. He, too, was a sales man, and we had to go through dire periods of unemployment, health challenges, boarding schools, nurseries, loneliness, etc. I realize only now that it was the bond between us which gave my father meaning in his otherwise so complicated life. He did say many times that I was most important to him, but I never really understood until I read Martin Buber: The world is not comprehensible, but it is embraceable: through the embracing of one of its beings. My father embraced me and we somehow managed to get by, although the price we both paid was high.

The historian Yuval Harari writes in Sapiens that Huxley’s disconcerting world is based on the biological assumption that happiness equals pleasure; and we can extend our pleasant sensation by manipulating our biochemistry and refers to what psychologist Martin Seligman called the pleasant life. He continues that a meaningful life can be extremely satisfying even in the midst of hardship, whereas a meaningless life is a terrible ordeal no matter how comfortable it is. Seligman ads to the meaningful life the engaged life, i.e. identify your highest strengths and talents and recraft your life to use them as much as you can in work, love, friendship, parenting, and leisure.

Sagmeister lives an engaged life par excellence, but from a Christian viewpoint Harari concludes, he and the vast majority of people are in more or less the same situation as heroin addicts, like a man standing for decades on the seashore, embracing certain ‘good’ waves and trying to prevent them from disintegrating, while simultaneously pushing back ‘bad’ waves to prevent them from getting near him.

He is though equipped with a strong executive focus, a focus that enabled him to complete a film over a period of seven years despite many other projects and obligations. I think that his embracing of projects must be balanced with the embracing of people to give meaning. He fails with people, I fail with projects. People like Sagmeister are described with attributes like grit, while people like me are rather seen like douchebags.

I sincerely hope that our societies become more inclusive and as such embrace people like me; people who can’t execute like a Sagmeister or a Gardner. People who fail in competitive systems; students who fail in university entrance examinations; or even quit their lives. The Bangkok Post wrote yesterday after the suicide of 27-year old Korean singer Kim Jong- Hyun that by 2020 1.2 million people will take their lives annually with 20 times more attempts and an unknown number of people thinking about making an end to their life. Why are psychologists and parents worried that teenage Thai fans imitate their idol? It seems that our cultures have gone down the wrong path and it is our duty to correct them. Not everybody can become a rockstar designer or a prolific wall street broker.

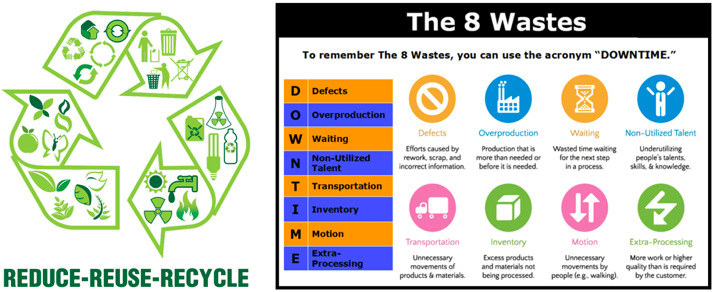

Let's be clear about this: The world also doesn’t need too many of those. There is though much meaningful work to be done. One might not earn a grammy for such work, but the feeling of satisfaction and a life purpose. And we can all start today or tomorrow. Any day is good. As we have more time to rest, longer vacations, or as we are completely out of our jobs, we can embrace not only our partner, our children or our friends, but also mother Earth, our common home. Green folks talk a lot about recycle, reuse, reduce, but I meet few people who start to remove the waste and debris that clutters streets, forests and beaches.

City life makes us believe that municipal waste collection is the norm, but it is actually not. Here in rural Thailand large plastic containers without lids are placed before most houses, none are at the beaches. Plastic bags and fast food containers float through the air, kicked back and forth by the wind for which most tourist come here. Back in 2014, when we were here the first time, I was so taken aback that I started to collect myself. Soon about 20 people from many different nationalities, most of them from the local kitesurfing crowd, joined in and we cleaned a 100 meter long stretch of beach from all the debris. We lit a probably slightly toxic bonfire and burned our bounty that night. It was in hindsight the manifestation of a post-national purpose for mankind: clean our common home.

The solitary beach cleaning yesterday gave me time to think about all the items which I picked up. I learned that its psychologically more rewarding to start with big garbage chunks; and its smarter to remove large pieces first, before they can dissolve into smaller ones. I found dozens of lighters, flip flops, bottles and cans of all sizes, beverage straws, and many items I could not make sense of, collecting in total on a stretch of 20 meters of beach eight Ikea bags of debris.

I left with a sense of both satisfaction and self-sacrifice. Why am I collecting waste while locals and other tourists alike don’t seem to care? Eventually the self-sacrificial voice fell silent and satisfaction remained. I hope that such meaningful occupation will soon be rewarded by our societies with a basic universal income, making it actually feasible for teenagers to engage in purposeful activities and even earn a modest living therewith. We could give urban suicide prone youngster the opportunity to move to the countryside for re-education; very much like once Mao Zedong in the 1960s but without using force. The Washington Post reports that similar things happen in the US, where the 1990s slackers are increasingly substituted by young farmers.

It seems as if Mao, the visionary from hell, was half a century too early with this cultural revolution and it also seems as if we need to reinterpret what 20th century philosopher Buber wrote about embracing the other: the other is for 21st century humanity not necessarily another human being but the entire ecosystem we are part of. It can be as such a patch of land which we make ours or a stretch of beach where we spend our holidays. Both, economist Schumacher in A Guide for the Perplexed and psychologist Goleman in Ecological Intelligence pointed at this change in focus.

For self-leadership to get results you need all three kinds of focus. Inner focus attunes us to our intuitions, guiding values, and better decisions. Outer focus smooths our connections to the people in our lives. And other focus lets us navigate in the larger world. Being tuned out of one’s internal world you will be rudderless; one blind to the world of others will be clueless; those indifferent to the larger systems within which they operate are blindsided. Your focus is your reality. [Daniel Goleman]

It was about a year ago that I saw this clip when researching on the future of work. It was produced by a Thai life insurance company, and the creative director was clearly endorsed with a lot of freedom to convey not only his employer's but also his own message which is a beautiful version of the Bhagavad Gita saying that all our work, whether it is service at living creatures or mother Earth, we shall perform without expecting any reward in return.

We are again in Thailand and I will try to continue 2018 in this mindset and hope that more people join in. Watching this clip and documentaries like Plastic Ocean will help.