Joaquin Phoenix is Jonze’s accomplice in this coup d’art. The mentally fragile and hyper-sensitive Theodore is up till now one of the three exquisite performances for which he will be remembered (the other two are Commodus in Gladiator and Johnny Cash in Walk the Line). Its ironical that Rooney Mara, the woman which he divorces in Her, is since 2016 his real life partner. Bones, flesh and memories were more attractive than Scarlett Johannsson’s sexy OS voice.

So, where are we know? The most striking observation when watching this film only five years after its release is simply that it is not anymore futuristic, no it almost seems to be a bit outdated. That’s what exponential technological change means: Its beyond our grasp. News is heavy with much scarier and rather not so romantic dystopias. A Japanese man married last week an anime hologram, another one married last year a video game character in a VR wedding ceremony. An increasing number of Japanese men prefer virtual companions over real women and Bloomberg reports that virtual partners fill in Japan - the most urbanized and in many social developments leading (or most neurotic) country on this planet - a romantic void.

Since the rise of e-commerce in China, Singles Day has turned into a consumption madness, which generated this year for Jack Ma’s Alibaba platform alone more than USD 30 billion. A holiday which is supposed to celebrate bachelorhood becomes a day to celebrate consumerism. Isn’t that a quite significant coincidence? It seems as if our souls have turned into vast waste dumps, into black holes which suck up the material world to compensate for spiritual emptiness.

The boxing coach of a friend of mine bought supplies for the next six months and spent on Sunday four hours to unpack and check his purchases. He told my friend that he thinks of double eleven as a new Chinese tradition, and probably his unpretentious assessment is not far from the truth. As the US and China converge in their economic systems, citizens become primarily consumers who celebrate the post-modern traditions of capitalism: Black Friday (aka Cyber Day) and Singles Day. How deep though must the spiritual void be that we have to fill it with all this stuff?

Why do I bring up Singles Day when writing about Spike Jonze’s film? Well, it seems that after all what we call spiritual emptiness is far from spiritual, but a rather quite physical dent in our human makeup. The consumption of goods compensates for the lack of companionship; from an extreme point of view we could say that Singles Day celebrates the absence of partnership and love and as such has become the annual climax ritual in a culture of narcissism.

The Business Insider writes that 'Sex robots' are on the rise — and experts say we need to start talking about the consequences, in particular if these bodies are matched with the intelligence of Siri, Alexa, Cortana and other algorithms. What we really need to talk about though is the etiology of this sickness, not so much about symptoms or consequences. The Neolithic revolution has destroyed tribal hunter and gatherer societies. The industrial revolution has gradually vaporized what was left of human communities and we are left with the increasing isolation of postmodernism. What we lack is human touch. Love and being loved by another human being.

The Jewish theologian Martin Buber was therefore probably right when he said that The world is not comprehensible, but it is embraceable: through the embracing of one of its beings. What he meant with this single sentence some 70 years ago does make in a 21st century world of increasing complexity even more sense. Most of us are not brilliant Stanford computer science graduates who easily juggle the balls of science, technology and finance. Most of us are more mammals than transhumanist swots. What we want is peace, safety and belonging; and we don’t care about eternal life or superhuman powers.

Increasing physical distance between human beings and love’s elusiveness is the cause for why sex robots and personal operating systems are promising businesses. Increasing isolation is the cause for a need to compensate with stuff, whether it is a sex doll or a gigantic, golden wrapped package of super sweet mid-autumn cookies. Or is the economic system in which we are embedded the cause for increasing isolation? When we nowadays discuss if humans should be allowed to marry video game characters, what happens if AI is injected into sexbots, if chatbots need a license to provide psychotherapy, if operating systems who know us better than we know ourselves are a blessing our a curse, if we discuss all these questions we don’t see the forest for the trees. The most significant question we need to discuss is this: how do we get people to connect again with each other?

Technology does alter human relationships. This is a fact. We lose the competence of inward reflection and critical thinking when under the spell of a deep learning system which anticipates our grace and grind. This is a fact. Engaging in more human-machine relationships does not only change our ability to bond with other human beings, it even decreases the probability that we do so. This is not yet a fact, because no scientific evidence has been collected yet, but psychologists like Daniel Levitin point into this direction: The cost of all our electronic connectedness appears to be that it limits our biological capacity to connect with other people.

I have to quote again Martin Buber who said that mental illnesses do not grow in but between people. If he was right then more connection to stuff which translates in 21st century language to IoT, i.e. the Internet of Things, is detrimental to mental health. Forget about your fitbit. Take a slow stroll and chat with somebody. It’s not only Buber, there are many more serious philosophers and scientists who confirm that more human connection and more lasting human connections are essential to longevity and well-being. Dan Buettner pointed this out in his National Geographic Society project on so called Blue Zones, i.e. areas with an outstanding number of centenarians. Psychologist Robert Waldinger, Director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development, did so in one of the most comprehensive longitudinal studies in history.

Buettner writes in a NYT article about longevity on a Greek island that “In the United States, when it comes to improving health, people tend to focus on exercise and what we put into our mouths — organic foods, omega-3’s, micronutrients. We spend nearly $30 billion a year on vitamins and supplements alone. Yet in Ikaria and the other places like it, diet only partly explained higher life expectancy. Exercise — at least the way we think of it, as willful, dutiful, physical activity — played a small role at best. Social structure might turn out to be more important. In Sardinia, a cultural attitude that celebrated the elderly kept them engaged in the community and in extended-family homes until they were in their 100s. Studies have linked early retirement among some workers in industrialized economies to reduced life expectancy.”

While Her seems to be a love story, it is in truth a film about the general state of human connectedness, and mental health data shows that maintaining this human connection increases in difficulty with proceeding age. There are many more septuagenarians and octogenarians suffering from loneliness than 39 year-old Theodores. We have created societies which make it difficult to engage and stay engaged in relationships. Designer Tristan Harris says the problem isn’t that people lack will power; it’s that there are a thousand people on the other side of the screen whose job it is to break down the self-regulation you have. We have created a technology driven culture which destroys all lasting forms of interpersonal structures. Giving Samantha, Siri, Erika, etc. a sexy voice is only the first step in this game.

Universal Prostitution?

I make here an explicit statement, because this blog is mainly about the future of work and education and I keep asking what we will do when robots and algorithms do most of what we do now. Thinking a bit ahead and trying to understand the neurology of human well-being, there is no shortage of important work to be done. Spending time with each other, with elderly and with children will be more important than ever. Imagine kindergartens with a 2:1 teacher-student ratio, imagine most retirees being able to live with their families or in homes with one nurse for each inhabitant. Most people in employment age bracket between 15 and 65 could find a job in education, health or social work, if there were no other work to be done.

Getting paid for spending one’s time with another human being amounts to prostitution, and some people might criticize such an incentive. They might even sarcastically call the UBI then a universal prostitution income, i.e. UPI. But would it be wrong to pay such an income if we get more satisfaction, more meaning, less loneliness, less mental health issues and a generally healthier society? We have an ambivalent perception of what prostitution entails. Is it only selling one’s body or is there more to it? Prostitution is by some considered humanity’s oldest trade and it’s not only as old as the desire for another person, but probably also as old as the feeling of loneliness.

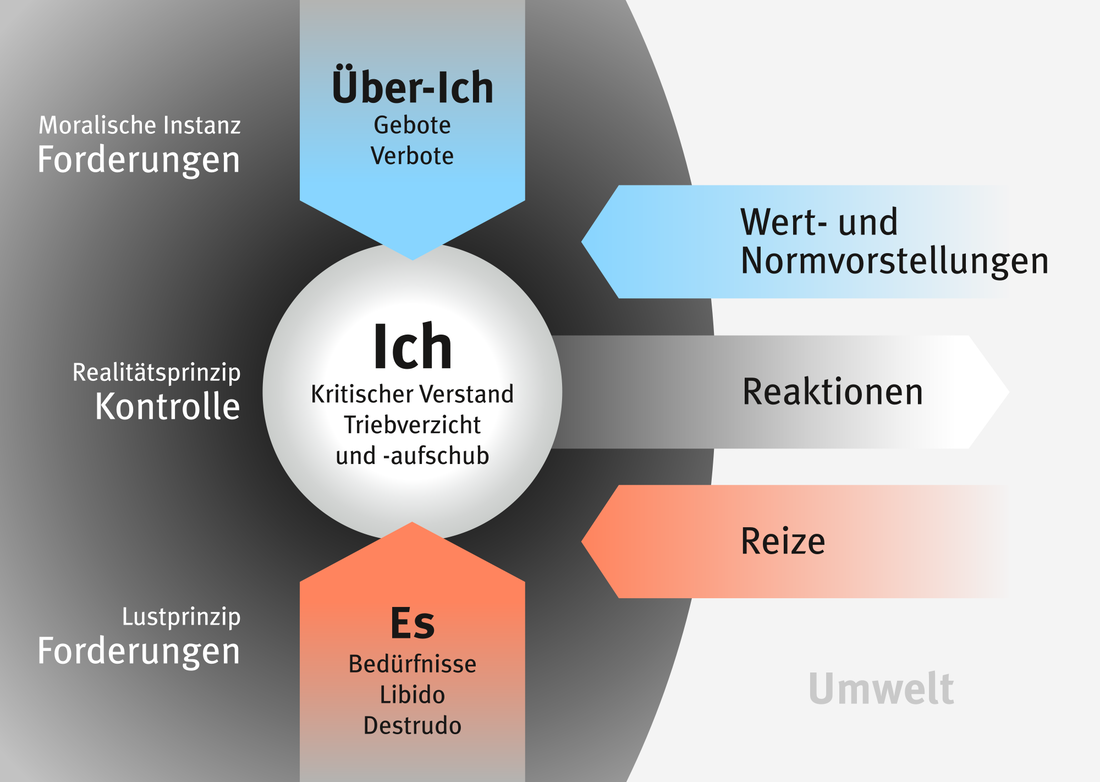

New York based relationship coaches Reid Mihalko and Marcia Kaczynski invented in 2004 so called cuddle parties, which is now a registered non-profit. People meet to embrace and pat each other without succumbing to sexual desire. Cuddle parties have since then spread as a social phenomenon throughout the Western world and could be characterized as the antipode to swinger clubs where participants go for a human touch instead for a beastly fuck. Some psychologists interpret the phenomenon as a reaction on man’s confused self-understanding which pushes the Id into an evil corner. The weakened ego suffers though under the moral expectations of the turbo charged postmodern superego. Cuddle parties are therefore the ego’s reaction to a society which prohibits the satisfaction of animal desires and requests to live saint-like lives. Theodore would have been a natural contender for such parties.

In other words, we need to take the burden off our shoulders to do the right thing. Its again Dan Buettner who poignantly recognizes the situation: The problem is, it’s difficult to change individual behaviors when community behaviors stay the same. In the United States, you can’t go to a movie, walk through the airport or buy cough medicine without being routed through a gantlet of candy bars, salty snacks and sugar-sweetened beverages. The processed-food industry spends more than $4 billion a year tempting us to eat. How do you combat that? Discipline is a good thing, but discipline is a muscle that fatigues. Sooner or later, most people cave in to relentless temptation. And this is not only true for nutrition, but also for social interaction, whether love, companionship or tribal belonging.

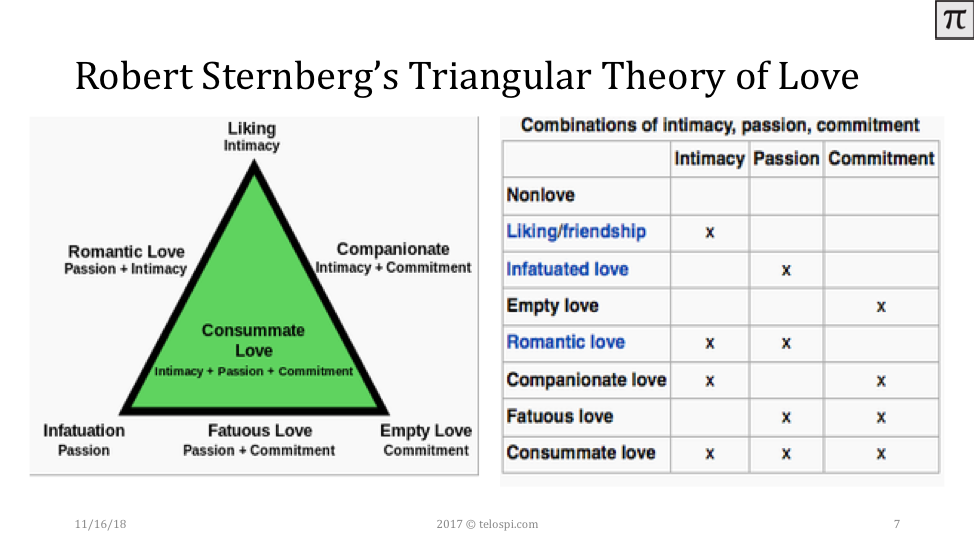

There is one more theme about Her which surfaced in connection with Ester Perel’s TED talk on how to maintain desire in a relationship. The Belgian psychotherapist explores since years the root of desire and has found that love and desire are incompatible in the long run. She thus disagrees with Robert Sternberg’s triangular theory of love and thinks that consummate love is not sustainable. Her explanation is simple: we project in modern relationships into one partner all the attributes of an entire village. We want him to be naughty lover, best friend, life coach, sometimes father, sometimes son, whatever we need in the emotional roller coaster that we call life.

Perel criticizes quite openly our atomized societies and pleads between the lines for a more open sexuality which enables people to live out their desires without having to fear losing the security of a stable relationship. She claims rightly that most of us struggle with an eternal conflict of needing security and companionship, but wanting adventure and the touch of the unknown. This is the conflict between superego and Id, which I described earlier. Journalist Christopher Ryan makes an argument on why we are designed to be sexual omnivores. I hear them and there is a lot of truth in what they say. We are on an evolutionary path and our species has been for most of its existence tribal and highly promiscuous. And it seems to be only sound to put one’s bet not only on one partner but on many.

The frustration which Theodore experiences with his wife and then with Samantha reflect this desire described by Perel to have a partner with whom we share all and everything. We invest hours, weeks, months and years, and are heartbroken when things don’t work out. We fall in love and then fall into dirt without any safety net. In the pre-Neolithic past, in particular in matriarchic societies, falling in and out of love might have been smoother than today; but I reckon that there were many who were like today left with no partner at all. The past was not necessarily better than the present. It was different.

Theodore appears in Her not only as a mentally fragile man, but also extremely absorbed in his own misery. A clinical psychologist would certainly attest him medium depression, substantial signs of rumination and significant lethargy. The only attempt he makes to connect with the outside world in the film is through his letters which he writes in his day job for clients in a very remote interaction. Apart from this he appears to have personal contact only with his neighbors who also happen to slide into divorce like him and his wife. Theodore certainly would have attended cuddle parties.

Social psychologist Erich Fromm once wrote a little book titled The Art of Loving. He describes there different layers of love directed at the self, one’s lover, one’s children, one’s parents, one’s friends, one’s work, etc. Spike Jonze’s love story lacks this colorful and multifaceted understanding of love. It is rather a mirror of a seriously narcissistic culture, which conditions us to love another person for our own sake. The other becomes an object which has to serve the purpose of satisfying one of my desires. Theodore’s wife reflects this understanding of herself as an object, when they meet a last time to sign the divorce papers by saying that she never felt she could be herself without being criticized. The next step for Theodore would thus probably be the purchase of a Harmony sexbot model.

Erich Fromm and Martin Buber perceived this as perverted form of love and emphasized that one’s own identity grows out of the love we give to others. Love is here the service rendered to another person in the first place and only in the second place what we receive. Buber thinks that we may address existence in two ways: (1) that of the "I" toward an "It," toward an object that is separate in itself, which we either use or experience; (2) that of the "I" toward "Thou," in which we move into existence in a relationship without bounds. One of the major themes of the book is that human life finds its meaningfulness in relationships. All of our relationships, Buber contends, bring us ultimately into relationship with God, who is the Eternal Thou.

Ester Perel, I feel, seems to be obsessed with desire similar like Sigmund Freund was obsessed with pleasure, but she explains perfectly well, why Theodore’s wife wants to divorce him: There is no neediness in desire. Nobody needs anybody. There is no caretaking in desire. Caretaking is mightily loving. It's a powerful anti-aphrodisiac. I have yet to see somebody who is so turned on by somebody who needs them. Wanting them is one thing. Needing them is a shot down and women have known that forever, because anything that will bring up parenthood will usually decrease the erotic charge.

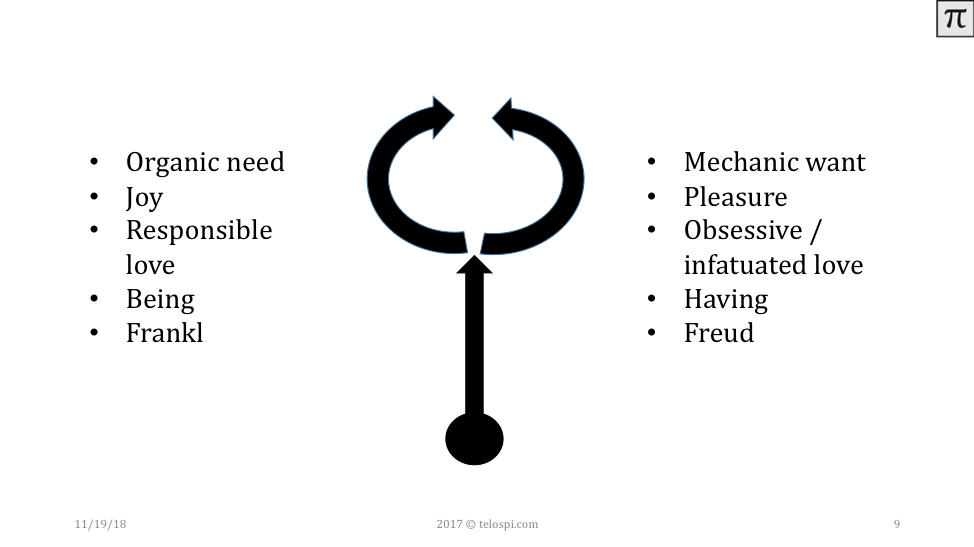

Overemphasizing desire leads to a serious neglect of commitment. There was another Viennese neurologist, Viktor Frankl, who countered Freud’s psychoanalysis. Harvard psychologist Gordon W. Allport writes in the foreword to Frankl’s seminal Man’s Search for Meaning: While Freud stressed the frustration in sexual life, Frankl stressed the frustration in the will-to-meaning. Frankl writes himself in The Unconscious God that man is in the last instance not interested in his inner condition, whether it is pleasure or emotional balance. He is directed towards the external world and he searches within this external world a purpose which he is capable to fulfill or a human being who he can love. Frankl thinks that we have an reflective ontological self-understanding which tells us that we can achieve self-realization only to such an extent as we forget ourselves. Forgetting oneself, he concludes, is a mental state which only emerges to such an extent as one yields to a purpose one serves or a person one loves.

While Freud’s psychoanalysis makes unconscious Id-drives conscious, Frankl’s existential analysis aims at making conscious a spiritual unconscious which is anchored in a sense of responsibility. Responsibility for another human being might mean in difficult periods of a relationship that somebody who has been desirable is now in serious need of caretaking; and the older we get this element in a relationship becomes more prevalent than desire. Why 60 year old Ester Perel is so obsessed with maintaining desire is a different question, but we need to maintain clarity about the nature of desire and the reason why commitment and purpose should outpace desire and lust.

Perel’s choice of words indicates her point of view on the TED stage: So if there is a verb, for me, that comes with love, it's "to have." And if there is a verb that comes with desire, it is "to want." In love, we want to have, we want to know the beloved. We want to minimize the distance. We want to contract that gap. We want to neutralize the tensions. We want closeness. But in desire, we tend to not really want to go back to the places we've already gone. Forgone conclusion does not keep our interest. In desire, we want an Other, somebody on the other side that we can go visit, that we can go spend some time with, that we can go see what goes on in their red-light district.

Contrary to Perel’s definition Fromm said that genuine love is not a having but a being. It’s not an emotion which is the result of fearing change. Responsible love is according to Fromm a dynamic emotion which embraces change. It’s an organic need which is juxtaposed to an mechanic and neverending want. Kogano Murata, a hermit bamboo flute player who is featured in Andy Couturier’s The Abundance of Less has a different perspective than Ester Perel: Reduce your baggage as much as you possibly can. When you get rid of your things you get easier in yourself, and you decrease your suffering more and more. But ‘I want, I want … ‘ That’s the beginning of suffering. In particular if your wanting is not supported by mainstream culture.

- Businessinsider: we need to talk about sexbots, expert say

- Bloomberg: in Japan, virtual partners fill a romantic void

- NYT on Siri, Alexa and other virtual personal assistants

- Singles Day explained on Wikipedia

- Scary only: My conversation with a sexbot

- Scary, but cute: Japanese man marries hologram

- Scary only: Touring a factory where sexbots come alive

- Dan Buettner on why people with lifelong friends live longer

- Dan Buettner on how a US citizen with terminal lung cancer turned 100+ upon returning to his Greek home island and reconnecting with his childhood friends

- Robert Waldinger on why genuine relationships are all that matter

- Robert Sternberg’s Triangular Theory of Love

- Psychotherapist Ester Perel on how to maintain desire in a relationship

- Anthropologist Helen Fisher on why we love and why we cheat

- Journalist Christopher Ryan explains why we are designed to be sexual omnivores

- The Art of Loving by Erich Fromm

- Man’s Search For Meaning by Viktor Frankl

- I and Thou by Martin Buber

- Richard Burger on Behind the Red Door: Sex in China

- Sinica on Business and Fucking in China

- James Palmer on why young rural women become mistresses in China

- The Unconscious God by Viktor Frankl

- Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl

- The Abundance of Less by Andy Couturier