Banit leaps through the history of AI in her broad US accent, uses industry terminology as if everybody must know and we feel that the audience seems to be sort of intimidated by her vocal presence and steroid train of thought. She makes gross use of the word AI itself and summarizes everything from simple algorithms over machine learning to super intelligence under the umbrella term. AI is the new oil, she tells us, therefore nations and corporations compete against each other in the race for resources, i.e. information about human beings.

We perceive AI rather than oil as the 21st century’s nuclear bomb: similar to Germany and the US before WWII, it is now China and the US racing for a technology which is deemed to give its owners ultimate power. And similar to the arms race before WWII which e.g. produced GPS as a now widely used civilian technology, we believe that big data and eventually also artificial general intelligence will bring for humanity enormous payoffs. We just have to hang in and avoid a WWIII.

2015 was according to Banit the breakthrough year, when main stream industry turned its investment artillery on the technology, Baidu rebranding itself as AI corporation, Facebook and Google kicking off an acquisition spree in the realm of small AI companies. China is about to close this gap in terms of business sector maturity, but lags behind in regard to technology development.

Top down industry policies like the 2015 promulgated 2025 Manufacturing Strategy have played an important role in China’s AI rush. Cash being set free at an astonishing rate for mostly immature and simple technology. Beijing’s commitment to transform the once manual manufacturing center into the world’s most intelligent manufacturing nation is firm and provincial as well as entrepreneurial resources are allocated accordingly.

Banit explains that machine learning was originally invented in Canada and can be considered as the first quantum leap into being able to apply computing power to real problems. The invention of machine learning can therefore be seen as the result of decades of basic research, which allows the incremental development of applications which can be commercialized.

We know from many other industries like PV cell manufacturing that Chinese companies don’t waste their time with basic research, but transfer such knowledge legally or illegally from abroad to its own facilities, where they excel in adding productivity and efficiency quite similar to their Japanese and Korean counterparts during the past decades. What we witness is thus in addition to a breakthrough technology an exponential multiplication of its applications because of China having set its eyes thereon.

How competitive is China’s AI industry then? The three industry giants Baidu in Beijing, Alibaba in Hangzhou and Tencent in Shenzhen have each carved out their own niche and have the advantage of the world’s largest single market as their resource. Baidu has locked in on autonomous vehicles, Alibaba on ecommerce algorithms and cloud computing, Tencent on social media, gaming and recently through a minority stake purchase from Tesla, e-mobility. Banit doubts thought that we will see more than commercialization coming from China.

Although Beijing pushes global giants, there might be also a future for smaller corporations, in particular because of the new Chinese cybersecurity law, which forces big data companies to make their data available to the Chinese government. The law reminds me though of earlier regulations in other industries. Indian and Chinese intellectual property law made e.g. exemptions to compulsory WTO and WIPO regulations in the pharma industry, when intellectual property rights create health risks to its population.

It the health of its population a concern for the Chinese government? Banit, who also sits in an international AI ethics commission, tells us that the race for AI is mostly driven by the Chinese governments objective to establish total control of its citizen. Total control sounds at least to me like an oxymoron to civilian health. Banit tells us that every corporation is evil, but what about governments? We believe Banit’s outlook is too gloomy after all. Every cloud has a silver lining and in times like these, we have to look at the bright side with particular focus.

It might have been the evilness of corporations and governments which made Andrew Ng leave Baidu this year; or his motivation to create lasting impact with deeplearning.ai, his education start up, which wants to bring AI skills to the masses. Moving into AI education does seem like an implicit revolutionary act which aims at breaking the cyberleninistic tendencies of the Chinese government: education as tool to break free from totalitarianism. Could have Pink Floyd anticipated such a development when they sang back in the 70s: We don’t need no education. We don’t need no thought control. Coders and robot engineers educated to hack the motherboard, the mothernationboard.

Despite Banit’s eloquence and her obvious immersion in the subject, we are left with the feeling that her passion of showing the threat of AI invading our privacy by creating a 1984 society and her gloomy outlook is somewhat similar to her countryman Yuval Harari, the historian who painted in Homo Deus an equally dire picture of mankind’s future. The reason therefore is probably her lacking understanding of consciousness which puts her certainly apart from Japanese AI researchers who mostly believe that machines can be self-conscious.

Like Harari, Banit Gal believes that most computer scientist and investors are driven by hubris, i.e. wanting to turn into God by creating a life form themselves. They design artificial intelligence in their own reflection and perpetuate what 19th century philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach already then said about religion: What man calls Absolute Being, his God, is his own being. We don’t want to go into the neoreligious movements of transhumanism and dataism at this point, although we do expect them to have ample room to flourish in China’s technocrat biotope.

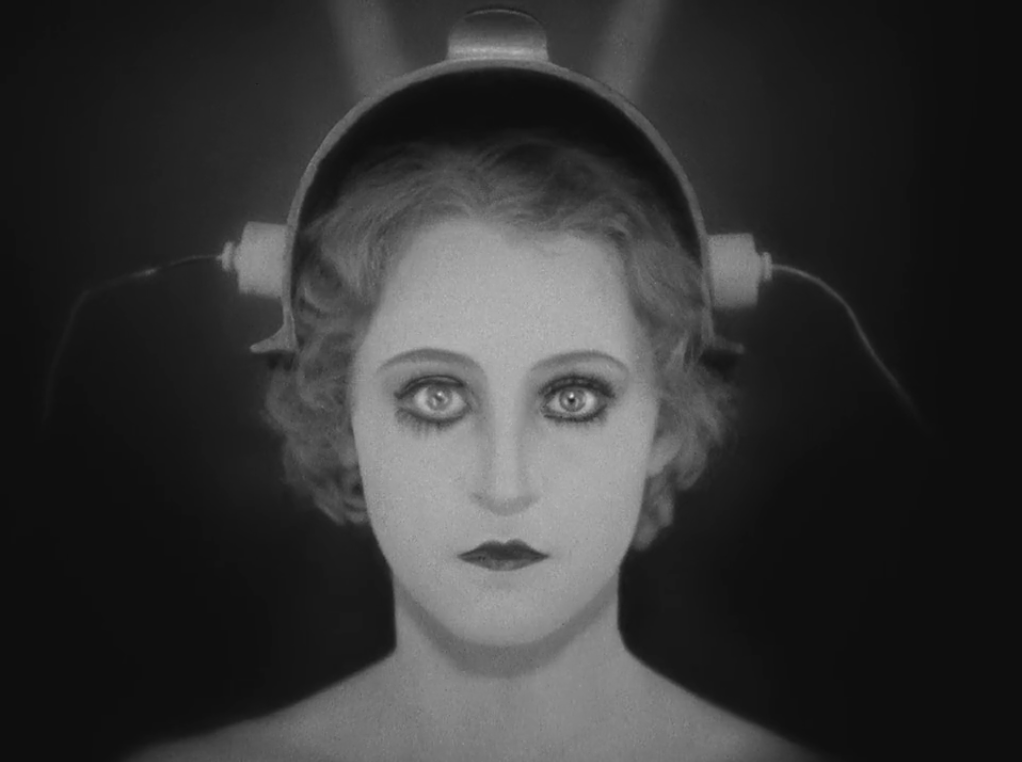

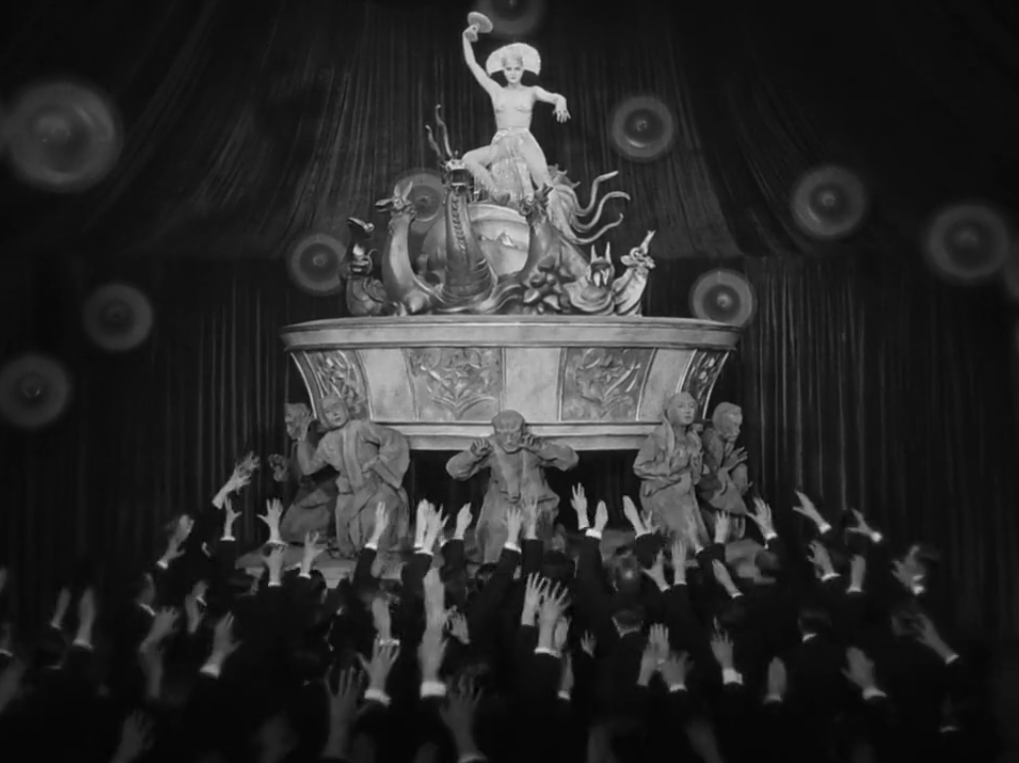

But, we would have wished for a more positive vision from such a young scientist like Banit and as we sit in a small round of man only, the situation reminding me of a scene in Metropolis, cornering a female tech scholar with additional questions after the main event, I ask her, if AI couldn’t be the solution to an environmental collapse. Even to this question Banit has a negative answer. She thinks that AI will consume vast amounts of electricity and thus will aggravate climate change.

We are more in line with economists like Andrew McAfee or Martin Ford, who sees the need for a universal income and thus the need for renewal of the social contract, because since Jean Jacques Rousseau came up with the concept in the 18th century at the beginning of the industrial revolution, our economies have transformed themselves from national entities to one global trading realm. What has happened in the economic sphere must follow ensuite in the social sphere.

Banit Gal thinks though that a universal income will never happen. Well, nothing we don’t hope for, will ever happen. Hope is the mother of all progress and was the only gift the Greek Gods put into Pandora’s box apart from all disease and misery with which they wanted to teach human hubris a lesson.

Further information:

- Center for Strategic and Internatioal Studies on Made in China 2025

- Li Kaifu on AI in China

- Andrew Ng on AI and China’s Start Up Culture

- Short, but very informative AI background paper by Amadeo Tumolillo at SupChina.

- Silicon Valley vs. China: Armsrace for AI Talent

- Roger Cremeers on Cyberlenisim and the Political Culture of the Chinese Internet

- Homo Deus by Yuval Harari

- Yuval Harari on Dataism and Free Will

- Andrew McAfee on the future of jobs

- Martin Ford on the Rise of Robots and a universal income

- David Schlesinger in Azeem Azhar's Exponential View on China and AI