Join our next event on January 10th, 2pm or every 2nd Sunday of the month.

It looked for many months like we would set up shop in the Berlin area, where we spent this year twice a few days as participants in a social impact accelerator financed by the Robert Bosch Foundation. We made friends in and with Berlin, but things unfolded differently. St. Poelten or short STP, the small provincial capital of lower Austria is as for now our European homebase. Lower Austria is to Austria – albeit on a different scale – what Hebei is to China: the province surrounds the nation’s capital. STP therefore looms in Vienna’s shadow like Shijiazhuang in Beijing’s.

In terms of transportation, infrastructure, access to nature and culture, STP compares better to Kunshan: it takes only 20’ to arrive by bullet train at Vienna’s main train station. Vienna gives to STP residents access to world class museums and music venues like the famous Golden Hall in a way Shanghai does to the many business which have chosen Kunshan for their operation. STP is removed from the hustle and bustle of larger cities. There are practically no traffic jams and almost everything can be reached on foot or by bike. While Kunshan is surrounded by the many lakes which are scattered between Shanghai and Suzhou, offering to its residents water sports and cycling as major pastime activities, STP is nestled at the intersection of four bioregions which invite to hiking and mountaineering in different landscapes.

STP reminds us of China in yet another way: the city is full of construction sites, and yellow cranes make up an intrinsic part of the humble skyline. A friend from exitgreen, a local sustainability organization tells us that STP deals with similar problems like cities in the YRD: it has the highest surface sealing rate in all of Austria and grows due to its proximity to Vienna and convenient public transport connection faster than any other city in this small country. Dynamism brings both opportunity and risk as we know from China: things can change fast for the better or the worse.

Rapid growth of urban spaces usually causes not only surface sealing but also the loss of commons. While we notice surface sealing and the construction of buildings as a manifestation of economic growth in the material world, the loss of commons spreads invisibly like a deadly gas and literally suffocates communities. Many years ago, when I studied in law school, I wondered about the psychological impact of property rights on our societies. Liberal economist like the famous economist-historian Niall Ferguson argue that property rights are an essential ingredient to create a civilization. I now think that property rights will be identified in future as both: the cause for a civilization’s rise and fall.

With the dissection of commons into small plots which belong exclusively to an individual or a corporation we destroy the integrity of the natural world and as such the possibility to connect to the planet. The more we retreat into the fake security of our own homes like fearful snails, the less we are able to connect to others and the planet. The capitalist property system creates a world of “little boxes” as political activist Malvina Reynolds sang in 1962.

A few years ago, Reynolds’ song was made a second time famous through the TV series Weeds, in which a suburban mother turns to dealing marijuana in order to maintain her privileged lifestyle after her husband dies. She finds out just how addicted her entire neighborhood already is. The TV series are a satire of suburban life but does also reflect how the property system creates a deprivation of shared space and thus community, which needs to be compensated with (drug) consumption.

We meanwhile know that our consumption habits are intrinsically related to our carbon footprint and therefore to climate change. Many try hard to live more sustainable lives, but we are caught up in the web of our societies which drive us into behavioral patterns of consumption and often unconscious compensation. The post WWII dream of the single-family home filled with appliances which make modern life enjoyable rests on the daily routine of commuting to the workplace and on the at least weekly routine of purchasing groceries in a supermarket or mall which is conveniently reached by car. We have given up self-reliance farming and completely and utterly rely on big retailers which dominate over the spectrum of our buyer decision.

Little boxes on the hillside,

Little boxes made of ticky-tacky,

Little boxes on the hillside,

Little boxes, all the same.

There's a green one and a pink one

And a blue one and a yellow one

They're all made out of ticky-tacky,

And they all look just the same.

And the people in houses

who went to the university,

where they were put in boxes,

And they all came out the same.

There's doctors and lawyers

And business executives,

They're all made out of ticky-tacky

And they all look just the same.

And they all play on the golf-course,

And drink their Martini dry,

And they all have pretty children,

And the children go to school.

And the children go to summer camp

And then to the university,

They all get put in boxes

And they all come out the same.

And the boys go into business,

And marry, raise a family,

And they all get put in boxes,

Little boxes, all the same.

Yeah a green one and a pink one

And a blue one and a yellow one

And they're all made out of ticky-tacky

And they all look just the same.

It is Reynolds who enchants us about the absurdity of suburban life and the boring monoculture it creates. Anthropologist Gary Snyder explains in The Practice of the Wild what commons are and why they are so essential for the integrity of the planet and our own soul:

The commons have been defined as “the undivided land belonging to the members of a local community as a whole.” This definition fails to make the point that the commons is both specific land and the traditional community institution that determines the carrying capacity of its various subunits and defines the rights and obligations of those who use it, with penalties for lapses. Because it is traditional and local, it is not identical with today’s “public domain,” which is land held and managed by a central government.

The commons is the contract a people make with their local natural system. The word has an instructive history: it is formed of ko, “together,” with (Greek) moin, “held in common.” But the Indo-European root mei means basically to “move, to go, to change.” This had an archaic special meaning of “exchange of goods and services within a society as regulated by custom or law.” I think it might well refer back to the principle of gift economies: “the gift must always move.” The root comes into Latin as munus, “service performed for the community” and hence “municipality.”

For the past two decades, I have spent my time in Austria mostly as tourist and was always amazed by its natural beauty. Quite often I asked myself, why I had traded it with heavily polluted and overpopulated Shanghai. Our recent neighborhood walks reveal though a different reality which goes unnoticed to the vagrant traveler: solid waste pollution is a growing problem. Pedestrians, cyclists and above all drivers litter wildly across the city whenever they are not in public view – a behavior which in my observation confirms that the property system disconnects inhabitants of an ecosystem from the moral responsibility to care for it. Spotless and meticulously designed front yards are in stark contrast to the “public domain” which is treated like an infinite garbage can.

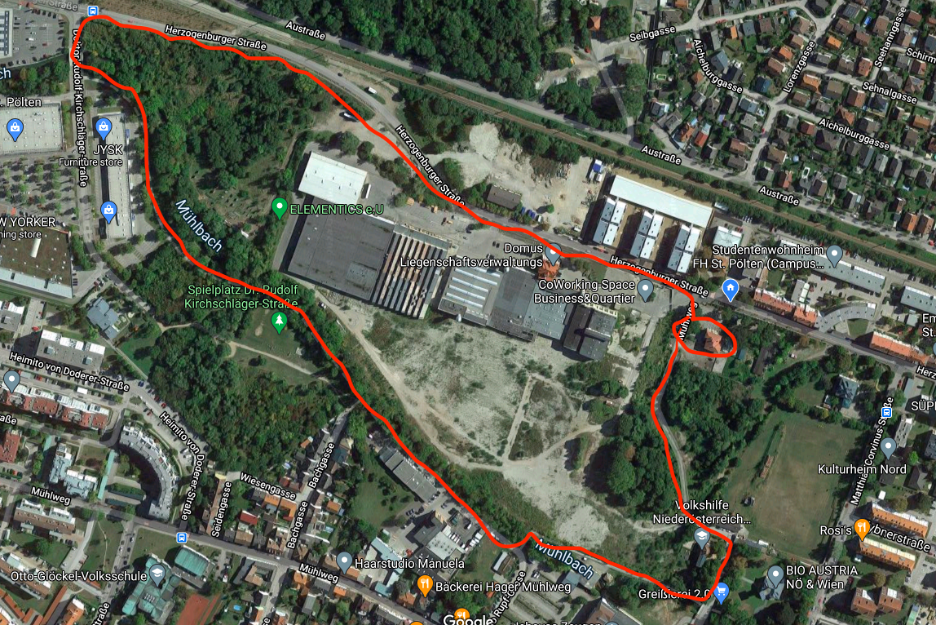

We have chosen the surroundings of a seriously littered former manufacturing site for textile fibers in alignment with our concept of environmental stewardship over commons. Glanzstoff Fabrik literally translates into brilliant fiber manufacturing company. It was up till 2015 a chemical producer of rayon, i.e. an artificial fiber which imitates the feel and texture of natural fibers such as silk, wool, cotton, and linen. As part of the United Rayon Factories is was occasionally in its more than one hundred yearlong operation the world’s second largest producer of rayon. Again, a connection to China, where most of the world’s fiber production has moved to. The process involves carbon sulfide which gave STP for decades the odor of rotten eggs. STP lost with the company a few hundred jobs but gained enormously in terms of living standard and treats its residents since then to a daily breeze of fresh Alpine air.

The Glanzstoff factory is now defunct and with its closing an ecosystem which lasted for more than a century collapsed. Despite the environmental burden which the operations put on the city and which were largely removed with national tax money in recent years, one needs to respect that the company created jobs and economic growth in the region. It showed responsibility for its workforce and financed community services, which included then state of the art residential buildings and a football club. A retired Glanzstoff employee who still lives in his old apartment told me that all the apartments had their own allotment garden. He praised the work ethic among his colleagues and lamented that things have changed a lot since the property is exploited to generate rental revenue.

A property management company has taken over and different scenarios have been sketched out to develop the plot into a modern residential neighborhood, but not much has been put into reality since the year 2009. Existing and new buildings are mostly let to different institutes of the nearby University of Applied Studies. Its very unlikely that the above master plan will ever materialize – and that’s probably good news for this part of the city, because one of the last – potential – commons of Northern STP would thereby be destroyed. On my regular stroll around the former manufacturing site I observe not only litter, but also deer, rabbits, beavers, waterfowl and a riverside woodland, which is in dear need of protection.

One can learn from China a great many things and use different ways of handling matters as an alternative to what we are used to. If corporations buy land in China, their deed is limited to 50 years and to the duration of business operation. Such a limitation of property rights might seem inconsolable with our Western understanding of exclusivity but applied on the case of the brilliant fiber manufacturing company, I think it’s a better model than the one we practice so far.

The original land-owning purpose of manufacturing fiber has been abandoned. More than a century has passed, and the situation of the plot and the needs of the surrounding community have changed. The new landlord has stopped to deal responsibly with the land he has purchased from a larger community, i.e. in the case of Glanzstoff the city of STP. Legal provisions should make it possible to take back what is not managed properly. The wild littering in the Glanzstoff area and a recent apartment complex which has been erected on a plot which was covered with old trees are proof of such an irresponsible attitude. The capitalist exploitation of the neighborhood is well known in the city government, but nobody dares to speak up and touch upon the sacred lamb of exclusive property rights.

- Damages: The defendant may have to pay monetary damages to cover the financial losses of the victim (such as hospital bills or pain and suffering)

- Restraining orders: A judge can issue a domestic abuse injunction such as a temporary or permanent restraining order. These can require the defendant to stay a certain distance from the victim, and can prohibit communication with the victim

- Rehabilitation courses: A judge can also require the defendant to attend mandatory rehabilitation courses, such as anger management classes

- Custodial rights: The defendant may lose their rights to child custody and visitation. This is true even if the charges involved spousal abuse, since courts aim to protect children from being exposed to violence

Somehow, our environmental laws have not caught up with the dire situation of the planet. As parents do not own their children, so do landlords not own a piece of the planet. We are gifted with our children and are asked to unfold their potential. Similarly, the stewardship over land is bestowed upon us in order to preserve its fertility or restore its integrity. A landlord who abuses his stewardship should

- lose his rights to use or exploit the land (withdraw ownership)

- pay monetary damages to cover the investments necessary to restore the integrity of the ecosystem (indemnify)

- attend mandatory rehabilitation courses about mindful land use and corporate social and environmental responsibility (rehabilitate).

Join our next event on January 10th, 2pm